|

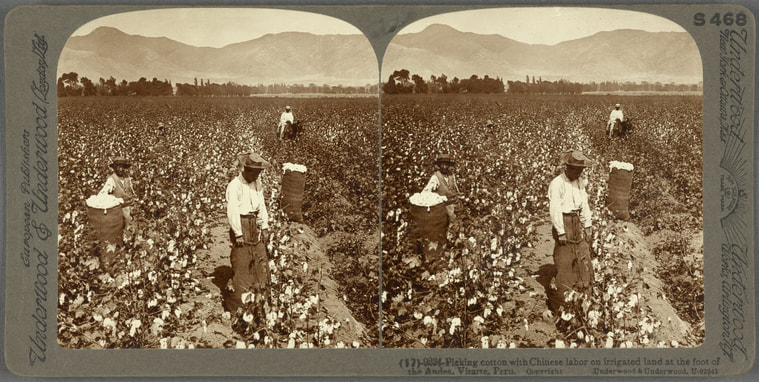

by Jolin Chan With over 45 million ethnic Chinese living outside China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Macau, as of 2013, the Chinese diaspora spans the entire globe, reaching every habitable continent[1]. The United States is the country with the largest Chinese population. Still, this statistic does not diminish the influence that the overseas Chinese community has on other countries and regions of the world. The stories, histories, challenges, and successes of Chinese Americans are widely known, but the presence of the Chinese diaspora in other parts of the world—from South America to Australia—should not be ignored. The Chinese-American experience is only one part of the Chinese diasporic experience. As Chinese people were pushed out of their motherland for political and economic reasons during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the stories of these immigrants can thus be found almost everywhere. Southeast Asia, as a region, has the most prominent Chinese diasporic population, with Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore taking the lead in numbers[2]. The Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia has always been closely intertwined with the economy, but it has roots in the political turmoil that China experienced in the late nineteenth century. China, crumbling under the pressure of the Opium Wars, the Taiping Rebellion, and Western imperialism, was unable to withstand the upheaval[3]. However, these socio-political push factors did not stop with the new century, as the Chinese Civil War and the war against Japan also influenced emigration to Southeast Asia and beyond. For these Chinese emigrants, Southeast Asia provided new opportunities, with some arriving in the region via the coolie trade due to the labor demand[4]. During the Ming dynasty, Chinese communities, mainly from the southern regions of China, settled in Southeast Asia to establish trade relations. These trade relations continued into the Qing dynasty, and the Chinese diaspora further established their presence as laborers, merchant middlemen, and traders of people and goods[5]. In the mid-twentieth century, the flow of emigrants from China stopped with the establishment of the People’s Republic of China and its new policies on emigration, but existing Chinese communities in Southeast Asia continued to grow and flourish[6]. For many of these Chinese immigrants in Southeast Asia, their identities can be encapsulated by the term luoyen guigen, or “fallen leaves return to their roots.”[7] In other words, their loyalty still lay with China, their motherland, and cultural practices were still deeply rooted in what they remembered from China or what had been passed down from generation to generation. Because of this, and due to the Cold War and the economic prosperity of the Chinese immigrants, there was often anti-Chinese sentiment that stemmed not from their appearance or any visible difference but because of their socioeconomic status, which came from a history of working as traders and middlemen[8]. Strained relationships between Southeast Asia and China are historically rooted in the tributary system during imperial China, in which unequal relationships were cultivated between China and areas that are now present-day Thailand and Vietnam, for example[9]. These tensions were carried into the twentieth century due to the growing ethnic Chinese population (and their growing nationalism), as well as the interference and influence of the People’s Republic of China in Southeast Asian politics during the mid-century[10]. For example, with the onset of the Cold War, Thailand took on an anti-communist stance, and Prime Minister Plaek (Phibun) Phibunsongkhram enacted anti-Chinese policies and campaigns. This was in reaction to China’s interference in domestic politics and in fear of China possibly expanding to Southeast Asia[11]. More violent displays of racism were not uncommon. In Indonesia, not only were the Chinese (and the indigenous population) segregated by the Dutch, which limited the facilities they could use and the areas they could settle in, but there were also violent acts targeted at the Chinese population[12]. For example, in 1740, Europeans of the Dutch East India Company killed more than 10,000 Chinese residents in what is now called the Batavia Massacre. In the twentieth century, anti-Chinese sentiment remained and manifested in anti-Chinese riots and discriminatory policies, specifically from the New Order with the rise of President Suharto, which banned the Chinese language and suppressed Chinese culture[13]. Despite the long history of discrimination, and similar to the diasporic community in the United States, the Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia was able to carve out a space for themselves, retain parts of their culture, and find a community. Colonial expansion and European demand for Southeast Asian products during the nineteenth century allowed their businesses to thrive, and organizations called huiguan (會館 / 会馆) emerged and helped communities find solidarity through shared dialect, hometown, and culture[14]. In Southeast Asia, the Chinese diaspora found ways to adopt parts of the local culture and maintain strong ties with their motherland. Since the late twentieth century, Sinicization—the revival of Chinese culture—has been a growing phenomenon within the community due to the easing of Cold War-era cultural suppression and China’s new efforts to connect with Southeast Asian Chinese communities[15]. On the other hand, life in Latin America for the Chinese diaspora was not unlike life in the United States. It is also deeply intertwined with the anti-Chinese sentiment that was happening in the United States, as the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 forced many immigrant laborers to head to Latin America instead. Like with the Caribbean, the decline of slavery in the mid-nineteenth century, as well as China’s decline and political unrest, resulted in large-scale migration of Chinese laborers, who were used to replace the old labor force. Chinese workers signed contracts that forced them to work four to eight years or longer and became part of the hacienda system. These migrants, part of the coolie trade (or la trata amarilla, the “yellow trade,” in Spanish), often worked on sugar and cotton plantations or mined guano (used to produce gunpowder and explosives), labor-intensive work that helped fuel the trade for cash crops but also resulted in exhaustion and ill-treatment[16]. Like in the United States, Chinese laborers often experienced abuse and maltreatment, but the government was often on the side of the planters. While they were seen as cheap and efficient labor, they were not seen as desirable subjects or citizens[17]. This naturally came with protest and resistance, shown through stealing, running away, striking, or purposely disrupting production[18]. These Chinese workers eventually finished their contracts and moved to cities, where they found jobs as domestic workers, business owners of stores and restaurants, and artisans, to name a few examples[19]. They also integrated into Latin American culture. For instance, in Peru, the majority of the Chinese male immigrant population entered relationships and had mixed-race offspring with Peruvian women, who mainly were Amerindians and Black. These mixed-race relationships and Chinese-Peruvian offspring, however, resulted in racist reactions and were seen as “racial degeneracy.”[20] Still, the Chinese diaspora in Latin America was able to thrive. There was both adoption of culture (learning the country’s language), fusion of culture (chaufa in Peru, for example, which consists of a mix of Chinese and Peruvian cuisine), and bringing in culture (such as Barrio Chino, a Chinatown, in Mexico). Another part of the globe, Oceania, also experienced Chinese migration. The largest Chinese diasporic communities reside in Australia and Hawaii. Some of these communities, namely Hawaii, have histories rooted in the coolie trade. Many Chinese migrants—as mentioned before—worked on plantations in the Americas, and one of these hotspots was Hawaii. Arriving as contract laborers for sugar plantations on the island or businessmen interested in the sugar industry, many Chinese immigrants settled on the land. They formed a community during the nineteenth century[21]. Anti-Chinese sentiment also emerged in Hawaii from both Hawaiians, who were being displaced from their land, and white plantation owners and businessmen, who felt threatened by the growing presence of Chinese immigrants and thought that they were corrupting native Hawaiian society[22]. The Hawaiian government also enacted limits on Chinese immigration, which led to more laborers from Japan, Korea, and the Philippines entering. Similar conditions—the labor shortage—led to the Chinese diaspora in Australia, but before that, some Chinese came as servants and artisans and found jobs as shopkeepers, cooks, and fishermen, to name a few examples[23]. Another pull factor, however, was the gold rush that started in 1851, only a few years after the California Gold Rush. For the latter half of the nineteenth century, Chinese miners came to Australia and worked in mines looking for gold, copper, tin, and other mineral resources. Like in California, anti-Chinese violence erupted, such as the Lambing Flat riots, in which European miners attacked Chinese camps, burned their belongings, and beat up Chinese miners[24]. In 1901, the White Australia policy began restricting Asian (specifically Chinese) and Pacific Islander immigration. Despite this, Chinese presence in Australia remained strong with the formation of Chinatowns. Putting these stories of Chinese diasporic communities side by side, despite the distance that separates them geographically, illuminates that not only do they come from the same country, but they also have similarities in push and pull factors, experience with racism, and successes and struggles. When these histories are taken from isolation and put into conversation with each other, the stories highlight patterns and parallels that cross national boundaries and oceans. However, just as it is critical to recognize these parallels and continuities, it is equally important to acknowledge the multitude of stories from the Chinese diaspora across space—different countries, states, cities—and time—from generation to generation. References

Academy for Cultural Diplomacy. “Chinese Diaspora Across the World: A General Overview.” https://www.culturaldiplomacy.org/academy/index.php?chinese-diaspora. “CHINESE STORE,” Digital Archives of Hawaiʻi. Photograph. https://digitalarchives.hawaii.gov/item/ark:70111/48cK. Cho, Il Hyun, and Seo-Hyun Park. “The Rise of China and Varying Sentiments in Southeast Asia toward Great Powers.” Strategic Studies Quarterly 7, no. 2 (2013): 69–92. Dongen, Els van, and Hong Liu. “The Changing Meanings of Diaspora: The Chinese in Southeast Asia.” In Routledge Handbook of Asian Migrations, 1st ed., 33–47. Routledge, 2018. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315660493-2. Glick, Clarence E. Sojourners and Settlers: Chinese Migrants in Hawaii. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2017. Hu-DeHart, Evelyn, and Kathleen López. “Asian Diasporas in Latin America and the Caribbean: An Historical Overview.” Afro-Hispanic Review 27, no. 1 (2008): 9–21. http://search.proquest.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/scholarly-journals/asian-diasporas-latin-america-caribbean/docview/210683828/se-2?accountid=11311. Hwang, Justina. “Chinese in Peru in the 19th Century.” Brown University Library. https://library.brown.edu/create/modernlatinamerica/chapters/chapter-6-the-andes/moments-in-andean-history/chinese-peru/. Liu, Hong. “Opportunities and Anxieties for the Chinese Diaspora in Southeast Asia.” Current History 115, no. 784 (2016): 312–18. Look Lai, Walton, and Chee-Beng Tan. The Chinese in Latin America and the Caribbean. Brill, 2010. Mathew, P. A. “In Search of El Dorado: Chinese Diaspora in Southeast Asia.” China Report 48, no. 3 (2012): 351–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009445512462310. Mo, Yimei. “Harvest of Endurance: A History of the Chinese in Australia 1788–1988.” Making Multicultural Australia. https://www.multiculturalaustralia.edu.au/library/media/document/id/298.Harvest-of-Endurance-A-History-of-the-Chinese-in-Australia-1788-1988. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. "Picking cotton with Chinese labor on irrigated land at the foot of the Andes, Vitarte, Peru." New York Public Library Digital Collections. Photograph. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/5e66b3e9-1f21-d471-e040-e00a180654d7. Tanasaldy, Taufiq. “From Official to Grassroots Racism: Transformation of Anti-Chinese Sentiment in Indonesia.” The Political Quarterly 93, no. 3 (2022): 460–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.13148.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

|

Pacific Atrocities Education

730 Commercial Street San Francisco, CA 94108 415-988-9889 |

Copyright © 2021 Pacific Atrocities Education.

We are a registered 501 (c)(3) charity. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>