|

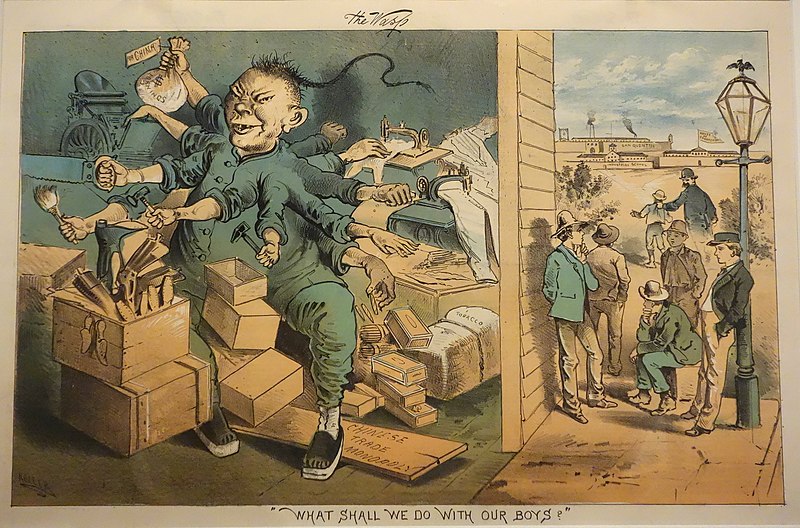

by Jolin Chan The Chinese diaspora has a long, complex history, encompassing six continents spanning hundreds of years. The simple categorization of Chinese immigrants as "overseas Chinese" often belies the multiplicity and heterogeneity of the group, as well as the many forces that influenced their movement, including colonialism, imperialism, and war. These forces pushed them to all parts of the globe, from Peru to Malaysia, and at the same time, they brought their language, food, traditions, and beliefs along with them—but not without facing resentment and xenophobia. Though the Chinese diaspora is often thought of as a nineteenth-century and twentieth-century phenomenon, it has roots in the Maritime Silk Road. A truly global route, up to the fifteenth century, the Maritime Silk Road connected China, Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent, the Arabian Peninsula, Africa, and Europe. It not only allowed people to transport and trade goods, but it was also a catalyst for Chinese immigration to Southeast Asia, a region that would continue to be a popular immigration destination—even today—and the region with the most overseas Chinese. [1] Chinese immigration has also always been intertwined with labor. The second wave emerged from British imperialism and the Opium Wars. As colonizing powers such as Britain promised to bring liberalism, rights, free trade, and more via their expansion into Asia, Africa, and the Americas, they brought new forms of labor systems and bureaucracy that oppressed the native peoples of the colonized lands, transformed them into commodities, and deemed them as inferior.[2] The many unequal treaties that China signed with Western powers forced them to open up, and though China was never an official colony, foreign powers had control over international settlements or treaty ports.[3] Furthermore, in Hong Kong, which did become an official British colony, policing and regulation were important strategies employed by the colonial government. These strategies, as well as new laws, "treated all Chinese as transient migrants" and "installed Europeans as the legitimate 'inhabitants' of the island."[4] The advent of abolition in England did not mean that inhumane, dehumanizing labor came to an end. Instead, the Crown needed to search for a new source of free labor, specifically for their West Indies colonies. Thus, Britain turned to Asian laborers to fulfill their demands. They were called "coolies," a pejorative term for unskilled laborers typically from India and China. To the British, the Chinese diaspora served two purposes. One, importing Chinese laborers would allow them to continue their production in their colonies. And two, they were thought to be useful for "suppress[ing] Black slave rebellion."[5] Colonial administrator John Sullivan described Chinese people as "a free race of cultivators… who, from habits and feelings could be kept distinct from the Negroes,"[6] thus becoming a "' racial barrier' between [the British] and the Negroes.'" More than just a movement of people, the Chinese diaspora and the history of the coolie are intricately intertwined with the slave trade and empire. To solve the labor shortage on colonial plantations, Britain looked toward coastal cities like Hong Kong and Canton (modern-day Guangdong) for male workers. However, these men also were not willingly working for the empire, some had been "either decoyed into or physically abducted and then sold into slavery."[7] Some were headed to Peru, some to Hawaii, and others to the Caribbean—to name a few destinations. Not only was crossing the Pacific Ocean dangerous and taxing, but the Chinese men were treated terribly, suffering from hunger, exhaustion, physical punishment, and more, which led to many deaths and suicides.[8] Others, however, went through towkay, or emigration brokers, to travel from Hong Kong and Canton to America. These emigrants had different journeys, although the trip across the ocean was equally harsh. They landed in San Francisco in the mid-1800s, marking America's first major wave of Chinese immigrants. They had their sights set on gold, dreaming of Gum San ("Gold Mountain")—the solution to their problems and the sources of their (fantasized) future wealth. In San Francisco, the Chinese men made their own community from the ground up, which grew in size as thousands of more Chinese began arriving in the city. They spent hours every day panning for gold; a few succeeded, but most did not, with some even committing suicide rather than return to China without newfound wealth.[9] At the same time, other immigrants would become entrepreneurs, work in agriculture, and work in factories. What did emerge from their presence—and reputation for being hardworking—was xenophobia, or more specifically, Sinophobia. Americans viewed the Chinese incomers as enemies and competitors for both gold and jobs. California enacted legislation and taxes that targeted and charged Chinese miners.[10] Beyond legislation, Sinophobia manifested in horrific acts of violence that occurred throughout the country. The Chinese Massacre of 1871 occurred in Los Angeles after a shootout between several Chinese men and policemen, and when a civilian named Robert Thompson helped, it resulted in Thompson's death. In reaction to his death, hundreds of rioters attacked and harassed Chinese residents. Eighteen Chinese people were killed, with most of them hanged, in what is often seen as one of America's largest lynchings.[11] Furthermore, what appeared in popular media and culture aptly reflected the growing anti-Chinese sentiment. In 1876, the Los Angeles Herald published an article about the "Anti-Coolie Club," whose mission was to "protect the white people residing in America from Chinese labor in any form, to discourage and stop any further Chinese immigration and to urge the withdrawal of the Chinese from the country, using only lawful means to attain these objects."[12] Other media included racist and xenophobic illustrations that portrayed Chinese immigrants as hostile, dirty, immoral, and monsters. However, despite the hostility, the people who stayed carved out a new home in California, establishing new neighborhoods ("little China" or "little Canton"), grocery stores, restaurants, and laundries. After dreams of the Gold Rush faded, America moved on to dreams about the transcontinental railroad, a system that would connect the country from one coast to another. There were obstacles one after another, and two companies took up the task: the Central Pacific Railroad Corporation (heading east from Sacramento) and the Union Pacific (heading west from Omaha). The two were to meet in the middle, at Promontory Point, Utah, but they needed more labor. Again, they turned toward Chinese men. Chinese immigrants provided cheap labor and were willing to do grueling work. Yet, they also served another purpose for the Central Pacific: a reminder to white workers that they were replaceable, thus causing another racial rift.[13] The Chinese laborers not only had to deal with hostility but were also working in dangerous conditions, for long hours (often from sunrise to sunset six days a week), and with hazardous material (such as nitroglycerin, an explosive that took many Chinese workers' lives).[14]

This was their life in America, but they did not simply stay rooted in the West. Chinese immigrants also began moving to the South and toward the East. Yet, even as the scenery changed, the challenges did not: hard labor, racism, and oppression. These anti-Chinese sentiments were clearly expressed through new laws and legislation during the late nineteenth century. The United States, with its long history of exclusion and racism, passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. This act became the first federal legislation that restricted immigration, and more specifically, it restricted immigration based on race. The reason why? Rising numbers of Chinese people worried white organized labor since many thought their jobs and livelihoods were being threatened. This fear turned into hostility as riots, massacres, and violence against the Chinese community exploded throughout America. The act specifically banned laborers, but even non-laborers found it incredibly difficult to enter the country. However, between 1882 and 1943, 85,000 Chinese immigrants were able to enter the United States, either because they were students, government officials, or people who found loopholes or purchased false papers. [15] The Chinese Exclusion Act was also just one example of the United States using laws to justify exclusion and xenophobia. The act established a ten-year ban on Chinese immigration but had a longer history and impact. It was extended for another ten years through the Geary Act, and then made permanent in 1902, with the addition of more restrictions.[16] Even though immigrants continued to enter the United States, Congress heavily monitored their movement through quotas and requirements. It even infamously expanded the limits on immigration to cover other Asian countries and Southern and Eastern Europe via the Immigration Act of 1924 or the Johnson-Reed Act.[17] Only in 1943 would the United States pass the Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act, also known as the Magnuson Act, and end these quotas. However, the legacies still live on. These journeys and challenges—largely from North America—are only one part of the Chinese diasporic experience. As Chinese people were pushed out of their motherland for political and economic reasons during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. 1. Zhuang Guotu, “The Overseas Chinese: A Long History,” UNESCO. 2. Lisa Lowe, “The Intimacies of Four Continents,” in The Intimacies of Four Continents (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015). 3. “China and the West,” American Historical Situation. 4. Lisa Lowe, “The Ruses of Liberty,” in The Intimacies of Four Continents (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 124. 5. Lowe, “The Intimacies of Four Continents,” 23. 6. Lowe, “The Intimacies of Four Continents,” 22–24. 7. Iris Chang, The Chinese in America (East Rutherford: Penguin Publishing Group, 2004), 30. 8. Chang, 31. 9. Chang, 36 10. “From Gold Rush to Golden State,” The Library of Congress. 11. Kelly Wallace, “Forgotten Los Angeles History: The Chinese Massacre of 1871,” Los Angeles Public Library. 12. Wes Keat, “The Anti-Chinese Club,” Los Angeles Herald. 13. Chang, The Chinese in America, 56. 14. Chang, The Chinese in America, 58-59, 61. 15. Shauna Lo, “Chinese Women Entering New England: Chinese Exclusion Act Case Files, Boston, 1911–1925,” The New England Quarterly 81, no. 3 (2008): 385. 16. “Chinese Exclusion Act (1882),” National Archives and Records Administration. 17. “Chinese Exclusion Act (1882),” National Archives and Records Administration. Bibliography Chang, Iris. The Chinese in America. East Rutherford: Penguin Publishing Group, 2004. "China and the West." American Historical Situation. https://www.historians.org/about-aha-and-membership/aha-history-and-archives/gi-roundtable-series/pamphlets/em-42-our-chinese-ally-(1944)/china-and-the-west. "Chinese Exclusion Act (1882)." National Archives and Records Administration. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/chinese-exclusion-act. "From Gold Rush to Golden State." The Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/collections/california-first-person-narratives/articles-and-essays/early-california-history/from-gold-rush-to-golden-state/. Guotu, Zhuang. "The Overseas Chinese: A Long History." UNESCO, September 21, 2021. https://articles.unesco.org/en/articles/overseas-chinese-long-history. Lo, Shauna. "Chinese Women Entering New England: Chinese Exclusion Act Case Files, Boston, 1911–1925." The New England Quarterly 81, no. 3 (2008): 383–409. Lowe, Lisa. "The Intimacies of Four Continents." In The Intimacies of Four Continents, 1–41. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015. Lowe, Lisa. "The Ruses of Liberty." In The Intimacies of Four Continents, 101–133. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015. Wallace, Kelly. "Forgotten Los Angeles History: The Chinese Massacre of 1871." Los Angeles Public Library, May 19, 2017. https://www.lapl.org/collections-resources/blogs/lapl/chinese-massacre-1871. Keat, Wes. "The Anti-Chinese Club." Los Angeles Herald, June 22, 1876. https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=LAH18760622.2.16&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN--------.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

|

Pacific Atrocities Education

730 Commercial Street San Francisco, CA 94108 415-988-9889 |

Copyright © 2021 Pacific Atrocities Education.

We are a registered 501 (c)(3) charity. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>