|

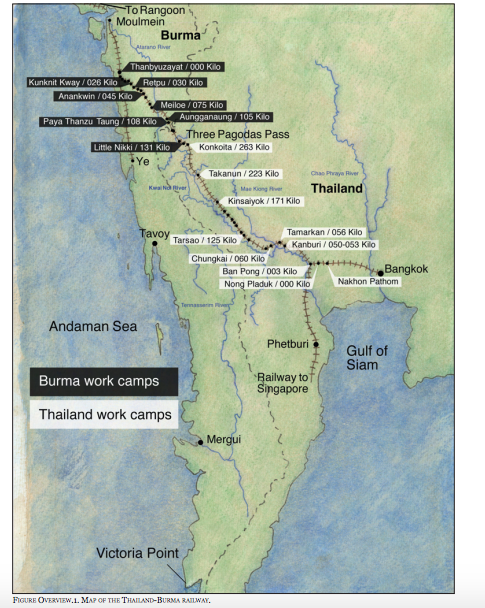

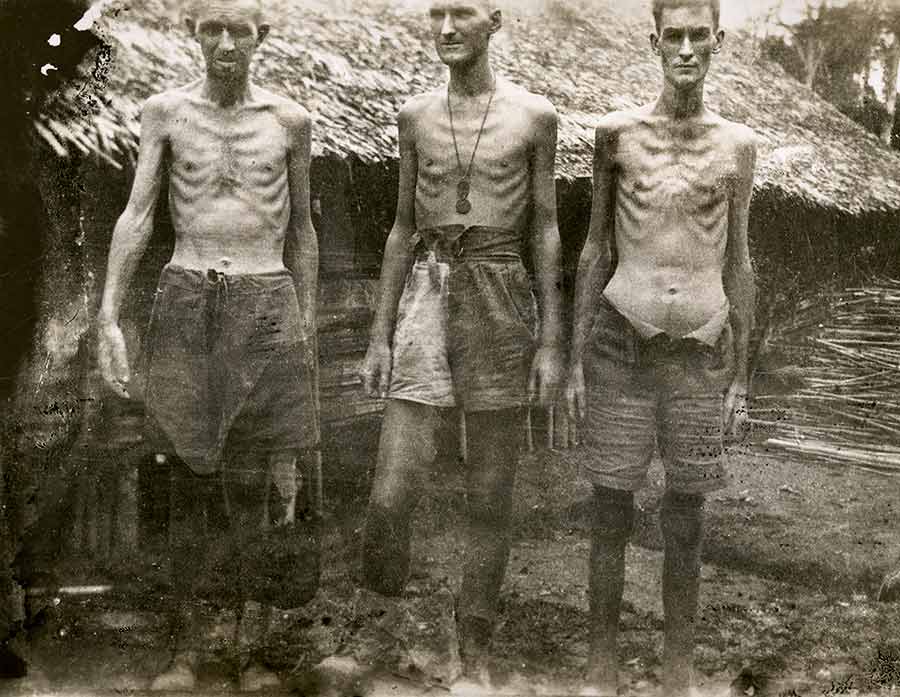

by Nickii Wantakan Arcado One day the war will be over, and I hope that the people who use this bridge in years to come will remember how it was built, and who built it. Not a gang of slaves, but soldiers! About a two hour drive from the capital city of Bangkok is the western province of Kanchanaburi. With an etymological name translating to “The City of Gold”, Kanachanburi is exemplified by its national parks, waterfalls, and elephant sanctuaries. Following the flow of the Khwae Yai river, spectators can gaze upon farmers tending to their rice patties or marvel over the natural landscape of hills and mountains in the backdrop of the city. But behind the façade of lush forestry, lies a horrific memory of World War II; the forced construction of a railroad system that took the lives of over 100,000 individuals. Wartime Strategy and the Birth of the Death Railroad As Japanese naval forces were weakened during the Battle of Midway and the Battle of the Coral Sea in 1942 causing passages such as the Andaman Sea and the Bay of Bengal to be occupied by allied forces, an alternative supply route was needed to sustain and assist the Japanese campaign in Burma. Japanese plans to build a rail line in somewhere in Southeast Asia began as early as 1939. Though building a railway connecting Thailand and Burma was not a new concept, efforts were abandoned as construction through dense jungles, rugged mountains, and turbulent rivers proved to be extremely difficult. However, in 1942 the Japanese Empire found a solution to this impasse; it would be using its 61,000 captured POWs, and another 300,000 Asian workers, as its labor force. Ignoring the Geneva Protocol that forbid using POWs for war-related activities, Japan rounded up captured Allied POWs from Singapore and Indonesian (formerly the Dutch East Indies) prison camps and immediately put them to work. Thailand’s strategy in building the railroad, along with its allyship with Japan, on the other hand, were the results of rising nationalistic sentiments. When the war broke out in 1939, unlike its position in World War I in which the country fought against the Central Powers, Thailand declared its neutrality. Both France and Britain were anguished of this decision, hoping that the country would help its efforts in protecting its nearby Southeast Asian colonies. At the time, Thailand was under the rule of Plaek Phibunsongkhram (commonly known as ‘Phibun’), a military leader from the People’s Party (Khana Ratsadorn) who had come to power after the 1932 coup d’etat that overthrew Thailand’s absolute monarchy in place for a constitutional monarchy. Phibun’s administration carried fascist overtones, illustrated by the tripling of the country’s military budget and introduction of nationalistic policies. A significant example was the 12 edicts (รัฐนิยม), one edict famously known for changing the country’s name from Siam to Thailand. Laws and cultural mandates that defined how to be a ‘proper’ Thai citizen began to emerge, encouraging a culture of segregation, ethnic discrimination and irredentist sentiments. Another example was the 1940 Franco-Thai war. While the regime’s domestic policies focused on chauvinism and patriotism, international goals were more irredentist. The regime called for the restoration of formerly lost territories in Laos, Cambodia and Burma, areas that were now colonies of the Allied powers. Along the eastern front (in provinces now known as Sa Kaeo and Ubon Ratchathani), war broke out between French and Thai forces. While American forces opposed the occupation, Japanese forces were supportive, using its partnership with Germany to coerce the Vichy regime to grant Thailand concessions. On March 1941, France agreed to cede Laotian and Cambodian territory to Thailand. Both event would later contribute to Thailand’s decision to sign the Treaty of Alliance with the Japanese Empire in 1942. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Japanese forces set foot in Thailand. Japan requested the right of passage through the country and access to Thai weaponry and equipment in exchange for territorial concession and trade deals with the Axis powers. With over 150,000 Japanese soldiers now stationed in Thailand and plans for the railroad about to commence, the country declared war against the Allied powers on January 25, 1942. However, despite the newly created alliance, the underground Free Thai (เสรีไทย) resistance movement--who protested the cruelty of both the Japanese Empire and current regime and the economic issues impacting the nation--gradually gained momentum in the shadows, aided by Allied operative groups. This resistance movement would later grow to over 90,000 individuals and assist the Allied forces in strategically bombing Japanese logistical encampments not only in Thailand but throughout Southeast Asia. The Plight of Allied POWs and the Romusha Although known officially as the Thailand-Burma Railway, the nickname “Death Railway” was adopted due to the high death tolls of POWs and Asian laborers in constructing the war-time infrastructure. Though records vary depending on statistical sources, approximately 14,000 Allied POWs and 90,000 Asian laborers lost their lives either due to horrific work conditions, starvation, vitamin deficiency, malaria, or dengue fever. While the British were amongst the highest number of Allied POWs deaths at 6,904 soldiers, it was Australian forces that were disproportionately affected. While 4,000 Australians were captured by German and Ottoman forces in Europe during World War I, more than 22,000 Australians were captured by the Japanese in the Asia-Pacific region. More than a third of Australian POWs lost their lives in captivity, totaling to 20% of all Australian deaths during World War II. Asian Laborers, known in Japanese as romusha, consisted of people from Burma, Thailand, China, and Indonesia and ethnic communities such as the Tamil, Java, and Karen peoples. Due to its proximately to Thailand, the largest Romusha percentage came Burma and Malaysia (formerly Malaya) with estimates being 90,000 and 75,000 respectively. In total, Japan had over 200,000 romushas at their disposal. Japanese recruitment for romusha initially began as paid contracts, with additional compensation in the form of food, clothing, housing. However, experiencing the physical and mental fatigue of building rail lines through uncharted terrain and the gradual decrease of monetary compensation from Japanese force, contractors began fleeing after their expiration dates. Fearing that the decrease of romushas would slow down construction, Japan soon changed their tactic into forced conscription of romushas. Unlike Allied POWs, romushas did not possess either military or educational backgrounds and as such were not as physically conditioned or informed of emerging health hazards. Furthermore, due to their large numbers, romushas camps became extremely crowded, prompting unsanitary conditions which produce high rates of illnesses and infection. Approximately 90,000 romushas lives were lost by the end of the construction period, 360 persons per mile of track laid on the Death Railroad. Unfortunately, contrary to their Allied POWs counterpart whose government focuses on their repatriation, romushas had difficulty returning to their country or places of origin. Despite being the largest workforce and experiencing the highest death toll, romushas did not obtain the same international recognition for their suffering, resulting in romushas wandering aimlessly in Thailand or starting a new life in different parts of the Pacific. Those who did return home were not able to leave the country until many years after the end of the war. The biographies and past experiences of romushas continue to remain in the shadows of World War II history. This is due in large part because many romushas were illiterate and non-English speaking, and thus, were unable to document their personal accounts or spread their stories to a larger international audience. Post-war Asian narratives also tended to focus on events that revolved around resistance, uprisings and heroic battle, overlooking memories of slavery and exploitation. Most recently, however, more scholarly and academic research have begun shifting its focus on the stories of romushas during World War II, creating spaces and opportunities for previously forgotten voices.  The Rising Body Count and Hellpass Fire The highest death count occurred towards the end of the construction period on 1943. Deaths had reached to over 20% of the workforce due in large part to unfavorable weather conditions due to monsoon season and vehement Japanese forces who wanted to get troops and equipment to forces in Burma to launch their India liberation campaign before Allied British forces could regroup. In addition, the quick completion of the rail line would potentially help the Empire’s prospective conquest of British India. This period became known as ‘The Speedo’, a Japanese transliteration of the word ‘Speed’. While a prisoner might have been expected to work ten hour days and drill a meter into mountain sides, soon increased to fifteen then eighteen hour days and three meters of drilling. Workers who were deemed slow or who failed to meet the day’s goal were subjected to harsh and gruesome physical punishment. During its completion, the railroad measured 415 kilometers (about 257 miles), beginning at Non Pladuk in Thailand and ending at Thanbyuzayat in Myanmar (now known as Burma). When rail lines were unable to be built around mountains, cuttings (the mechanical excavation and removal of rock material via digging or drilling) were required to continue the rail track. One of the most difficult and longest of these cuttings was Hellpass Fire. With the implementation of ‘Speedo’, forced laborers were required to work throughout the night, having only the light from oil lamps to guide their path. The name was coined after the loud noises, dark atmosphere, and shadows of tired prisoners reflected on mountain sides, reminiscent of popular depictions of hell. Excavation of Hellfire Pass done mostly by hand, and by the time of its completion, was some 75 meters (246 feet) in length and 25 meters (82 feet) in depth. Revisiting and Recollections The memories and history of the Death Railroad continue to live on. The Thailand Burma Center Railway Museum in Kanchanaburi, contain photographs, images, and blurbs of the horrors behind the railroad’s construction, while also searching as an ongoing research facility. The museum continues to build its database of past prisoners, including some 105,000 profiles of Allied POWs. The museum also annually sponsors personalized trips for relatives of those who worked to build the rail line, taking them as far as to the border of Burma. Across from the museum is the Kanchanaburi War Cemetery, where the bodies of some 6,900 POWs are buried, mostly that of Dutch, Australian, and British nationality. Movies like 1957’s The Bridge Over River Kwai and 2013’s The Railway Man also continue to present the struggles and narrative of those who’ve built the Death Railroad. While only parts of the railroad exists today due to bombings, reforestation, and demolition from the Allied side to pay for reparations, parts of the rail from between Nong Pladuk and Nam Tok was reopened in 1957 to serve as transportation for the local community. In particular, the bridge and train route over the Mae Klong ‘Khwae Yai River’ River (commonly known as the Bridge on the River Kwai) remains a popular tourist attraction. Even after 75 years, the memories of the Death Railroad will forever be ingrained via the sweat and blood of POWs and romusha on Thai soil. References

Related Articles

2 Comments

Patricia Bragdon

4/30/2019 09:35:16 am

I just discovered your website this morning while researching material on the Burma-Siam Railroad for a family article I am writing.

Reply

9/19/2022 09:49:15 am

TAMIL LEARNING AND INFORMATION CENTRE (TLIC)

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

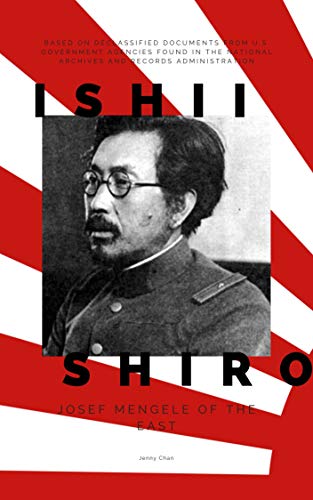

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

|

Pacific Atrocities Education

730 Commercial Street San Francisco, CA 94108 415-988-9889 |

Copyright © 2021 Pacific Atrocities Education.

We are a registered 501 (c)(3) charity. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>