|

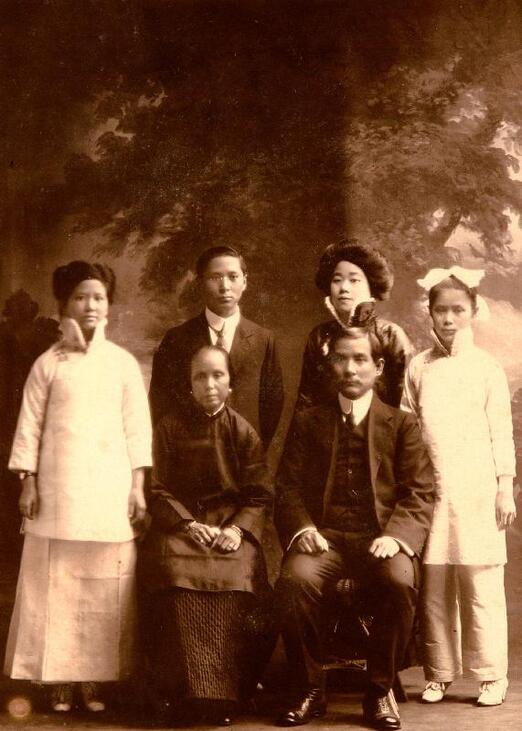

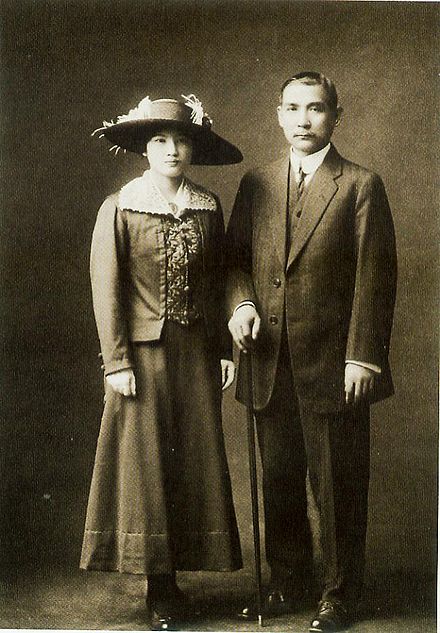

by Jolin Chan From ordinary men to political leaders to emperors, it was not uncommon before the Communist takeover in China for men to have multiple wives and concubines. The Kuomintang leaders were no exception, and their wives and mistresses proved to be more than simply idle partners of men with great political power and ambitions. Many of the wives and mistresses found ways to become deeply involved with the politics of China during their lifetimes, from helping their husbands or partners to taking on government roles that granted them immense power and voice. Sun Yat-sen, Chiang Kai-shek, and Wang Jingwei remain at the forefront of the history of the Kuomintang. Yet, the women that stood by their sides throughout the political turmoil played an essential role in determining the future of China. Many wives and mistresses from Soong Mei-ling to Chen Bijun found themselves not just during twentieth-century turmoil and political transitions. They also were instrumental in their country’s socio-political transformations themselves. Some of the women were pushed into the limelight, while others were forced to stay hidden and have nearly been forgotten. In the end, however, each of them left behind an important political legacy in a unique way. Sun Yat-sen 孫中山 Sun Yat-sen’s first wife was Lu Muzhen盧慕貞, a village woman his family chose for him in an arranged marriage that Sun claimed was a marriage of convenience (Pakula, 63). The two of them rarely spent time together as he was occupied with his work as a revolutionary, although they did have three children together: Sun Ke, Sun Yan, and Sun Wan (Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Museum). Because of Sun’s revolutionary activity and his failed uprisings against the Qing dynasty, Lu and their children were often at risk. She took them, as well as Sun’s mother, to live in Hawai’i with his brother. After funding many of Sun’s uprisings, his brother eventually became bankrupt and had to move to Hong Kong, where Lu and the children also went (Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Museum). During Sun’s exile in Japan, he met Kaoru Otsuki in 1898, when she was only ten years old. Several years later, after persistently asking her father for marriage, Sun finally got his approval and married Otsuki in 1903. Despite Otsuki having their daughter Fumiko two years after their marriage, Sun never publicly addressed their relationship and left Japan, effectively breaking off contact with Otsuki and his daughter. Otsuki, with little money and support, was forced to give away Fumiko for adoption (Japan-Revolution). It was only in the 1950s when Fumiko finally learned the truth about her parents, though she and her son—Sun’s grandson—were eventually able to connect with her past when they visited Kaoru before her death, Taiwan, and China in the latter half of the twentieth century. Before then, however, their relationship was kept a secret to avoid tainting his reputation (Japan-Revolution). While studying in Hong Kong, Sun met Chen Cuifen, who would become not just a longtime partner but also his “partner in revolution” (Chia). From 1910 to 1912, Chen joined Sun, Lu, their children, and Sun’s brother in Penang. Chen and Lu were said to have gotten along well and saw each other as sisters. Despite being relatively unknown in history, Chen greatly supported Sun. Not only did she care for him by cooking and doing his laundry, but she also risked her life helping him deliver secret messages and smuggle firearms. Even when Sun left Malaya, Chen went to Ipoh to fundraise for the revolution (Nasution, 92–93). Eventually, Sun met Soong Ching-ling宋庆龄 through his connections with the Soong family and because she was working as his secretary. Wanting to aid the revolution, Soong rebelled against her family to marry Dr. Sun. His family disapproved of him due to his age, and his previous marriages went against their Christian beliefs. She joined him in his exile in Tokyo, where she helped him as a translator and correspondent. Writing to a friend, she said, "I hope someday that all my labors & sacrifices will be repaid by seeing China freed from the bondage of a tyrant and a monarchist and stand as a Republic" (qtd. in Rosholt, 115). Sun quickly divorced Lu and cut off contact with Chen, who was banned from speaking about their relationship to protect Sun and Soong(Chia). Lu moved to Macau and eventually died there in 1952. As Sun went off to marry Soong and continue his revolutionary activities, Lu took on the responsibilities of raising their children and led a mostly private life (Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Museum). As for Chen, she moved back to Malaya, where she adopted a daughter. Despite Sun's abandonment, it is believed that she had kept two gifts of Sun's until her death: a ring and his watch (Chia). Her private life meant that she has largely disappeared into the depths of history, often seen only as a concubine rather than Sun's partner. As his new wife, Soong led an eventful life as a prominent political figure and Madame Sun Yat-sen. She continued to be politically active and supported Sun during his endeavors, using her education and experiences in America to act as a translator (Weisskopf). However, Soong's relationship with Sun created tension within the Soong family. Besides her parents' opposition to the marriage (Pakula, 65), she also disapproved of her brother-in-law Chiang Kai-shek's actions. Even after Sun's death in 1925, she remained deeply involved in politics. Soong supported the left wing of the Kuomintang and criticized Chiang's regime, despite her sister, Mei-ling, being married to Chiang. During the Sino-Japanese War, she founded the China Welfare Institute, organized hospitals, and raised funds. When Mao Zedong came into power in 1949, establishing the new People's Republic of China, he chose Soong to be one of the Vice-Chairmen of the Central People's Government Council (Weisskopf). Chiang Kai-Shek 蔣介石 Little is known about Chiang Kai-shek's first wife, Mao Fumei, a country girl five years his senior from Fenghua, Zhejiang. They had an arranged marriage in 1901 but ultimately divorced in 1921 (Fenby 22). During their marriage, Chiang met Yao Yecheng, a sing-song girl who became one of his concubines and later took on raising Chiang Wei-kuo, Chiang's adopted son (Fenby 43). As for Mao, despite the unhappy marriage, she bore Chiang's only biological son, Chiang Ching-Kuo. In the end, she was killed in a Japanese air raid in December 1939 at the age of 57 (Fenby xxvi).

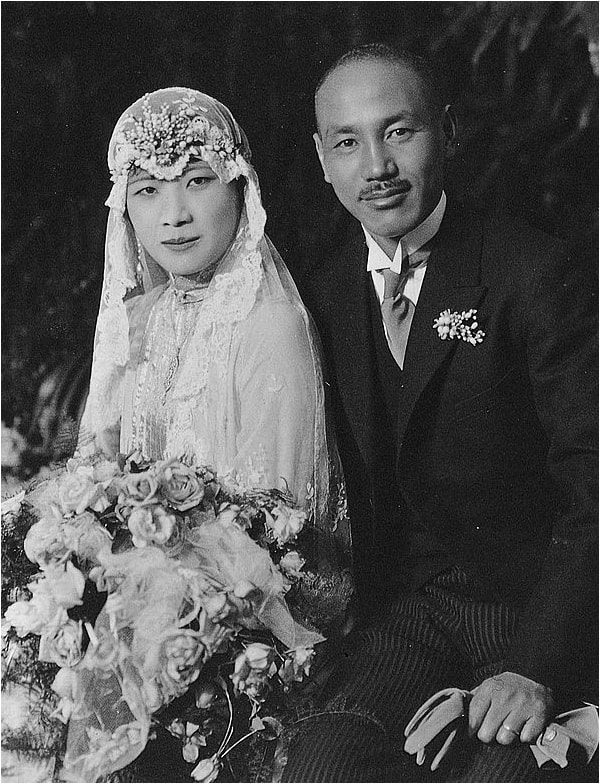

However, perhaps most people are familiar with Soong Mei-ling宋美齡. As Madame Chiang Kai-Shek, she was the face of China in the 1930s and 1940s, representing the new relationship between the United States and China. Having gone to school in America—attending Wellesley College—and lived in China after graduating, Soong acted as a bridge between the two countries. Even before her marriage to Chiang, Soong was well involved in politics. After Yuan Shikai took over China in 1912, Soong and her family joined the Kuomintang in Tokyo to help them strategize (Leong, 111-112). She remained active when the Soong family returned to China, where she joined reform efforts and participated in civic activities in Shanghai. Amidst turmoil during the 1920s, including protests, strikes, and political tension between and within groups, Soong and Chiang met. Their similar desire for China to become a modern nation resulted in a blossoming relationship, though their political interests also aided this. As a result, Soong's family could maintain their power and status, while Chiang could get a well-established family's support and become Sun Yat-sen's brother-in-law (Leong, 115-116). The two of them met while he was still married to Chen, but for him, the opportunity to marry Soong was too politically important to ignore. So he convinced Chen to attend an American college for five years, even promising that they would resume their marriage when she returned (Ch'en and Eastman, 238). After she left, however, Chiang denied knowing her and claimed that she was never his wife (Ch'en and Eastman, xv). She was heartbroken, and Soong and Chiang soon married in 1927. Soong was on her way to eventually become Madame Chiang Kai-Shek. Married to the country's new leader, Soong used her experiences in both China and the United States to help redefine a new China and to establish her role as not just the first lady but a powerful political figure. She worked with American and Christian organizations, initiated Western-style reforms, and encouraged Chinese women to participate in civic duty (Leong, 118-119). Faced with international attention, Soong used her unique background, powerful speeches, and diplomatic visits to rise to the forefront of nationalist politics and appeal to American audiences. Her efforts led to more American support during World War II and empowered many Chinese Americans, who held her and her accomplishments in high regard (Madame Chiang Kai-Shek's US Visit). Soong and Chiang worked together as a global power couple and even became Time Magazine's "Man and Woman of the Year" in 1937—though she herself would be considered the most powerful woman in the world in her own right (Garner). Chiang ultimately died in 1975, and after that, Soong led a more private life. She moved to Taiwan for a few years but ultimately decided to move to the United States, made occasional public appearances, lived to the age of 105, and died in New York. With a life that spanned three centuries, she left behind an immense legacy that is remembered by both China and America. Despite their different personalities and backgrounds, these women found their lives intertwined with one other, and their worlds were profoundly changed. Some started as a villager, a sing-song girl, or as part of China's socialite class. They all ended up in completely different places—one was killed during the war, some were forgotten as wives, and only one would become one of China's most powerful women Wang Jingwei 汪精衞 Like many of the other wives and mistresses, Chen Bijun 陳璧君 led an equally noteworthy and politically involved life as the wife of Wang Jingwei. They had met in Southeast Asia when Wang was working on anti-Manchu revolutionary work, and Chen eventually joined the Tongmenghui, an underground resistance movement and precursor to the Kuomintang. Chen and Wang met in 1907 and officially wed in 1912 when she was twenty years old (Yick, "Pre-Collaboration" 60). Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Chen remained close to Wang, accompanying and helping him as he worked for the Kuomintang (Yick, "Self-Serving Collaboration" 218). As a political figure, Chen gained a reputation for being strong, ambitious, forceful, and arrogant, and she even accepted being called "Mr. Chen" to emphasize her strength and to show that she was equivalent to other male political figures (Yick, "Pre-Collaboration" 60). When Wang Jingwei was a leader of the left-leaning Kuomintang faction and was the head of the Wuhan government, Chen took on the responsibilities and status of an unofficial First Lady of China. During this period, she helped her husband's regime combat Chiang, leading anti-Chiang movements and even acting as the lead negotiator in a settlement with Chiang (Yick, "Pre-Collaboration" 61). As his wife, Chen found ways to establish her power and influence, with Wang stating that "[She] is also my revolutionary comrade, and for that reason, I don't find it easy to make important decisions without considering her views" (Yick, "Self-Serving Collaboration" 220). During wartime, even as her husband was losing power within the Kuomintang, she was active in Guangdong in gaining military support for her husband and communicating with other Kuomintang leaders (Yick, "Pre-Collaboration" 63). Wang, however, was losing hope about successfully fighting against the Japanese. Chen participated in a secret meeting to negotiate peace terms with the Japanese, aided him in his escape to Hanoi, and began helping her husband establish his new government after officially breaking ties with Chiang Kai-shek (Yick, "Pre-Collaboration" 64-65). She played an extensive role in helping her husband establish puppet governments in Guangdong and Guangzhou while simultaneously advising him in his negotiations with the Japanese (Yick, "Pre-Collaboration" 70-71). Despite his initial involvement with the Kuomintang, Wang became anti-communist, switched his loyalty to the Japanese, and is known as one of the "Ten Big Hanjian (Traitors)" (十大漢奸). Chen would also find a place on this list, as well as the role of number one female traitor, for both her commitment to her husband and because of her own political actions and decisions during the war (Yick, "Pre-Collaboration" 59, 72). In the end, the Kuomintang tried her for treason but treated her more leniently because they thought she was simply a "loyal wife," sentencing her to life in prison rather than giving her a death sentence (Yick, "Pre-Collaboration" 59). During her trial, she firmly defended her and her husband's actions. She refused to admit guilt, which she would continue to do until her death in a prison hospital, even when she had the opportunity for freedom if she confessed to the new Communist government. She claimed, "I am willing to live out my life in jail," further cementing herself as a headstrong, determined woman and political figure (Musgrove, 24). Works Cited Ch'en, Chieh-ju, and Lloyd E. Eastman. Chiang Kai-Shek's Secret Past: The Memoir of His Second Wife, Ch'en Chieh-Ju. Westview Press, 1993, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/chiangkaisheksse00chen, Accessed 7 June 2022. Chia, Yei Yei. “Sun Yat-Sen's Lover Cuifen and Her Malaysia Villa.” ThinkChina, 16 Oct. 2019, https://www.thinkchina.sg/sun-yat-sens-lover-cuifen-and-her-malaysia-villa. “Chiang Kai-shek; Soong Mei-ling.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Soong-Mei-ling#/media/1/554625/96929. Accessed 9 June 2022. “Chiang Repudiates Woman As His Wife.” Chiang Kai-Shek's Secret Past: The Memoir of His Second Wife, Ch'en Chieh-Ju, Westview Press, Boulder, CO, 1993. “Dr Sun Yat-Sen Museum Tells Story of Dr Sun's First Wife, Lu Muzhen (with Photos).” Hong Kong SAR Government News, 20 Apr. 2012, https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/201204/20/P201204200485.htm. Accessed 7 June 2022. “Family of Young Chiang Kai-Shek.” Wikimedia Commons, 26 June 2011, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Family_of_young_Chiang_Kai-Shek.jpg. Accessed 9 June 2022. “Family Portrait of Sun Yat-Sen, Lu Muzhen, Their Children and Soong Ailing, Taken in Guangzhou in 1912.” Hong Kong SAR Government News, 20 Apr. 2012, https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/201204/20/P201204200485.htm. Accessed 7 June 2022. Fenby, Jonathan. Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-Shek and the China He Lost. The Free Press, 2003. Garner, Dwight. “Wartime China’s Elegant Enigma.” The New York Times, 3 Nov. 2009, https://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/04/books/04garner.html. Accessed 7 June 2022. “Japan-Revolution.” Asia Sentinel, 4 May 2011, https://www.asiasentinel.com/p/japan-revolution?s=r&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web. Leong, Karen J. “Mayling Soong.” The China Mystique: Pearl S. Buck, Anna May Wong, Mayling Soong, and the Transformation of American Orientalism, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA, 2005, pp. 106–154. “Madame Chiang Kai-Shek’s US Visit.” Museum of Chinese in America, https://www.mocanyc.org/collections/stories/madame-chiang-kai-sheks-us-visit/. Musgrove, Charles D. “Cheering the Traitor: The Post-War Trial of Chen Bijun, April 1946.” Twentieth-Century China, vol. 30, no. 2, Apr. 2005, pp. 3–27, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/788760/pdf. Accessed 8 June 2022. Nasution, Khoo Salma. “Dr. Sun's Family in Penang.” Sun Yat Sen in Penang, Areca Books, Penang, 2008, pp. 83–93, https://archive.org/details/sunyatseninpenan0000khoo. Accessed 7 June 2022. Pakula, Hannah. The Last Empress: Madame Chiang Kai-Shek and the Birth of Modern China. Simon & Schuster, 2009. “Portrait of Chen Cuifen in Changchun Pu Villa.” ThinkChina, 16 Oct. 2019, https://www.thinkchina.sg/sun-yat-sens-lover-cuifen-and-her-malaysia-villa. Accessed 7 June 2022. Rosholt, Malcolm. “The Shoe Box Letters from China, 1913-1967.” The Wisconsin Magazine of History, vol. 73, no. 2, 1989, pp. 111–133, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4636255. Accessed 7 June 2022. “Soong Ching-Ling, wearing cheongsam, in Shanghai after Sun Yat-sen's funeral.” Wikimedia Commons, 2 June 2010, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Soong_Ching-ling_wear_cheongsam.jpg. Accessed 9 June 2022. “Wang Jingwei & Chen Bijun Wedding Photo.” Wang Jingwei, The Wang Jingwei Irrevocable Trust, 20 Apr. 2020, https://www.wangjingwei.org/wang-chen-en/. Accessed 9 June 2022. Weisskopf, Michael. “Soong Ching-Ling, Widow of Sun Yat-Sen, Dies in Peking at Age 90.” The Washington Post, 30 May 1980, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1981/05/30/soong-ching-ling-widow-of-sun-yat-sen-dies-in-peking-at-age-90/b633dd93-08da-4a66-98e4-71f98819b86e/. Accessed 7 June 2022. Yick, Joseph K. S. “‘Pre-Collaboration’: The Political Activity and Influence of Chen Bijun in Wartime China, January 1938–May 1940.” Southeast Review of Asian Studies, vol. 36, 2014, pp. 58–74, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A427759259/AONE?u=mlin_m_hds&sid=googleScholar&xid=b87d8d91. Accessed 8 June 2022. Yick, Joseph K. S. “‘Self-Serving Collaboration’: The Political Legacy of ‘Madame Wang’ in Guangdong Province, 1940-1945.” American Journal of Chinese Studies, vol. 21, no. 2, Oct. 2014, pp. 217–234, https://www.jstor.org/stable/44289324. Accessed 8 June 2022. To learn more on how Soong & Chiang's relationship affected the Pacific Theater of WW2, check out:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

|

Pacific Atrocities Education

730 Commercial Street San Francisco, CA 94108 415-988-9889 |

Copyright © 2021 Pacific Atrocities Education.

We are a registered 501 (c)(3) charity. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>