|

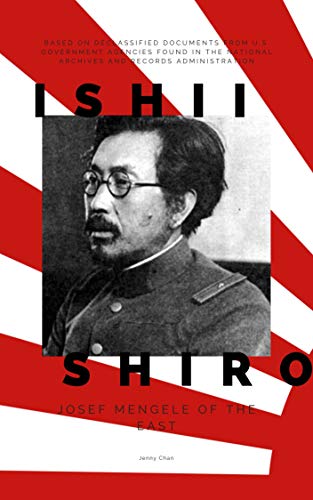

by Jack Gray The Japanese Imperial Government Disclosure Act of 2000, another name for Title VIII of the Intelligence Authorization Act of 2000, authorized the process of locating, declassifying, and publishing documents relevant to war crimes committed by the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II. (continued) Previously, the majority of research on World War II was focused on Nazi war crimes as President Clinton had created the Nazi War Criminal Records Interagency Working Group (known as the IWG) in 1998 to “to locate, inventory, recommend for declassification, and make available to the public all classified Nazi war criminal records.” The researchers of the IWG felt there was a need for additional research into Japanese war crimes, and asked permission to expand their activities to include this topic. Samuel Berger, Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs at the time, informally granted this request, which was later officially confirmed by President Bill Clinton. In 2000 the IWG was formally renamed the Nazi War Crimes and Japanese Imperial Government Records Interagency Working Group, and asked government agencies to examine their records for documents which could be relevant to Japanese war crimes. Specifically, they asked for (1) any materials related to Japanese Treatment of prisoners of war and civilian internees, including any materials related to forced or slave labor, (2) any materials related to development and use of chemical and biological warfare agents, (3) any materials related to General Ishii (the commanding officer of Unit 731), (4) any materials related to the U.S. Government decision after the War not to prosecute the Emperor and certain war criminals, and (5) any materials related to the so-called “Comfort Women” program, the Japanese systematic enslavement of women of subject populations for sexual purposes. This is why many of the war crimes are still being researched as the declassification didn't happen until the 2000s. After reviewing each department’s inventory, the IWG estimated that there were about two hundred thousand pages of documents that could be released—a far cry from the ten million pages of documents relating to Nazi war crimes. The reason for this disparity is different departments of the U.S. government have documents pertaining to different aspects of the war; the Department of the Army had greater autonomy over the Pacific theater and kept their own records, gradually releasing them during the 1970’s and 1980’s, whereas in Europe the Office of Strategic Services (the OSS) was largely in charge of intelligence, and had more stringent protocols for releasing documents. However, conventional intelligence agencies like the OSS and later the CIA (its successor) did play a role in the Pacific Theater. For example the Office of Strategic Services kept records about Japanese chemical and biological warfare and crimes against both civilians and prisoners of war, while the CIA kept records on Japanese intelligence efforts before and during the war. In addition to the recently released documents, there are many documents that have been available to the public since the end of the war. Most of these are transcripts or evidence from the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, which prosecuted individuals such as Tojo Hideki, prime minister of Japan during the war, General Yamashita Tomoyuki, who conquered Malaysia and the Philippines, or Lieutenant General Homma Masaharu, who commanded the Bataan Death March. Prosecutors used over 4,000 documents as evidence against the 28 defendants. Furthermore, many Japanese records from the war have been translated into English, thanks to the Allied Translator and Interpreter Section under General MacArthur, who were responsible for gathering and analyzing Japanese documents during and after the war. Unfortunately, many Japanese documents were destroyed by the Japanese themselves in an attempt to protect their leaders from prosecution for war crimes. More were lost when the U.S. government agreed to return a number of documents to Japan in the 1950’s and 1960’s. Although originally directed to complete their mission in one year, the IWG continued to work until April 2007, when they presented their final report to Congress. They declassified 1.2 million pages of documents relating to Nazi and Japanese war crimes. However, they considered their greatest accomplishment to be their proving that declassification of intelligence documents would not have drastic negative consequences, as was previously thought. U.S. intelligence services had long resisted the release of confidential information, concerned that it would endanger current efforts and operations, but the IWG felt they had shown that the release of historical documents would have no negative effects. The IWG also drew other large conclusions from their efforts. They showed that the reopening of documents and files is a massive, expensive, time-consuming effort, and recommended that all agencies continually review and follow protocols for declassifying their records instead of having to do large projects to search through decades of unopened files. The reason that these documents remain classified for so long after they became irrelevant was that there was a lack of public interest in Japanese atrocities before and during World War II. However, the stories of survivors and witnesses gradually gained momentum until the 1990’s, when a group of comfort women (women who were forced by the Japanese government to be prostitutes for Japanese soldiers) filed a lawsuit against Japan. In addition, Congress passed a resolution demanding that Japan issue both an apology for the crimes they had committed and pay compensation to surviving victims. However, Japan has never issued a formal apology, and did not provide restitution to their victims. The documents released thanks to the efforts of the IWG will be resources for researchers and historians who can shed greater light on this dark period of history. Hopefully by learning from the crimes of the past we can prevent any similar atrocities in the future. Further Reading https://www.archives.gov/files/iwg/japanese-war-crimes/introductory-essays.pdf This small book provides introductory essays to some of the more useful sources on Japanese war crimes that were released thanks to the Disclosure Acts. Most of the released documents themselves can be found on the National Archives Website at https://www.archives.gov/ References

Related ArticlesRelated Books

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

|

Pacific Atrocities Education

730 Commercial Street San Francisco, CA 94108 415-988-9889 |

Copyright © 2021 Pacific Atrocities Education.

We are a registered 501 (c)(3) charity. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>