|

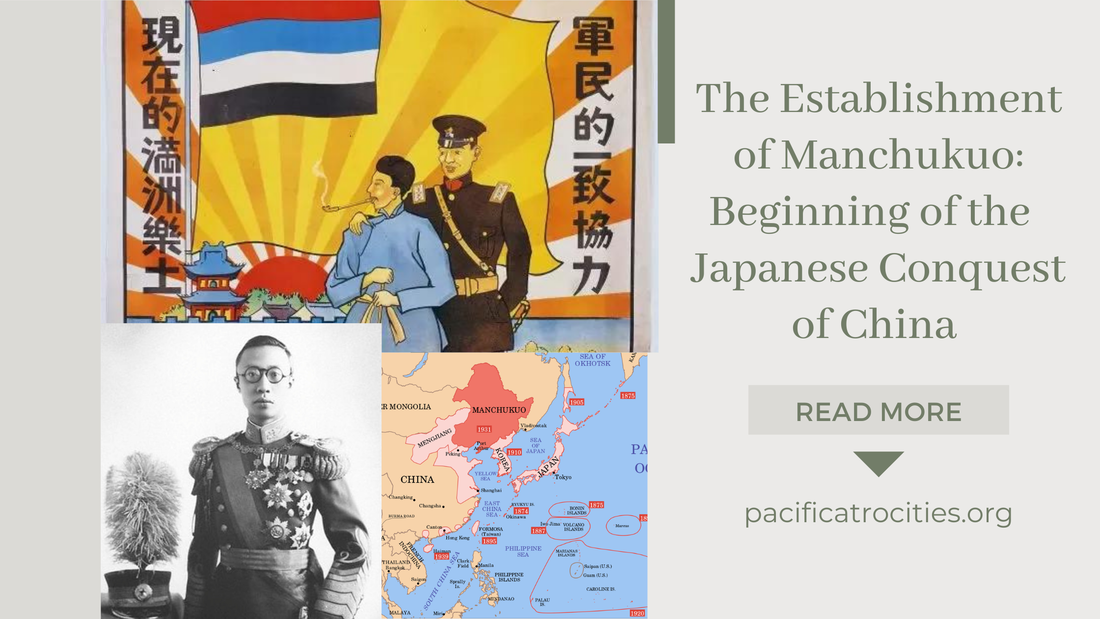

by Austin Chen On September 18th, 1931, Japan blew up a part of its own railroad built by the South Manchuria Railway, claimed that the Chinese installed the bomb, and outrageously attacked Manchuria. Shortly after this Invasion of Manchuria, Japan established a puppet state—Manchukuo—and invited the already deposed emperor—Puyi—as the leader of this new state. Though Japan was the actual controller of Manchukuo, Puyi was still the nominal emperor. Therefore, it is a firm question why Japan did not abolish Puyi and annex Manchuria into Japan's territory? Especially since the Empire of Japan had already annexed Korea, which indicated that annexation of Manchuria was possibly applicable. Before answering this question, let's start by knowing the importance of Manchuria since Japan coveted Manchuria, including Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning, for a long period. In 1895, after Japan's first victory in the Sino-Japanese War, Japan asked China to cede the Liaodong peninsula, the southeastern part of Liaoning Province, under the Treaty of Shimonoseki. Later, the Japanese cooperated with Zhang Zuolin, a powerful warlord, to better control the northeastern part of China ("Second Sino-Japanese War"). Japan's relentless effort in pursuing Manchuria was due to its strategic location. Manchuria shares borderlines with Russia in the north and with Japan's protectorate Korea in the southeast so that Manchukuo can be a buffer region between Russia and Japan. Therefore, Japan felt obligated to seize Manchuria because the presence of Russia, a European power, in Manchuria would substantially threaten Japan's protectorate of Korea and further threaten Japan itself (Gates 26). Moreover, Manchuria's abundant natural resources, especially iron and coal, of which Japan was severely in need of development industry, also attracted Japan (Mutter 8).

Because of its location and natural resources, Manchuria was the go-to place for Japan. However, Japan was not successful because occidental powers monitored and even interfered with Japan's movement in China (Mutter 4). This is the first reason Japan established a puppet state rather than annexed it. As we mentioned in the last paragraph, Manchukuo was close to both Russia and Japan, and both powers coveted it. They even fought for Manchuria: according to Hirosi Saito's account, "Japan had fight two desperate wars on Manchurian soil in 1894 and 1904 to ward off [Russia's] aggression and to secure her [Manchuria] own separate existence (Saito 161). "Russia was not the only one who competed with Japan: Germany forcefully landed in and leased Jiaozhou Bay, a port within Shandong, in 1897. Moreover, though western powers, along with Japan, collaboratively invaded China, they tried to maintain a sensitive equilibrium with one another, such that not any one country gained disproportionately larger benefits than the other country. For example, Great Britain expanded its Hong Kong colony in 1898, shortly after observing German, French, and Russia expand their colonies. Due to this sensitive equilibrium, Japan couldn't abolish Manchukuo and annex it into the Empire of Japan, as the Western power would not allow Japan to enjoy the benefits from China alone. Though the Invasion of Manchuria on September 18th, 1931, and the establishment of Manchukuo had already revealed Japan's ambition, Japan still wanted to use "independent" and "liberal" Manchukuo to conceal their greediness. Meiji Restoration enabled Japan to transform into an industrial country, yet it was ignored and even excluded by occidental countries as it is an Asian country instead of a European country (Mutter 4). Therefore, Japan had the mentality to build a "Greater Asia," and naturally, Japan's position was to "bring peace and security" to Manchuria (Gates 24). Japan learned from Great Britain's colonization model with minor revisions. Great Britain's colonization goal was to bring civilization, prosperity, and freedom to natives (Hase 2008). Therefore, Japan also utilized similar words to justify its full support of the establishment of Manchukuo. According to Hirosi Saito's speech, from the Japanese view, they gained nothing but contributed everything. Their contributions included but were not limited to Manchuria's peace, development of transportation system, education system, and industrial system (Saito 162). All these Japanese contributions would not be valid if Japan annexed Manchuria because the fact that Japan was not helping Manchukuo but merely tried to annex it would expose publicly, such that Japan's depiction of "independent" and "liberal" Manchukuo would be criticized heavily by other countries. Finally, another explanation of why Japan established Manchukuo, which prevails in Chinese history textbooks, pointed out that the establishment of Manchukuo broke Chinese land apart and, therefore, served as a good start for Japan to invade China further. This explanation is also sensible because when tracing the Japanese Army's further campaigns, we can notice that they were not satisfied with what they had already gained. Japan tried to go southward beyond the Great Wall. In 1935, Japan forced the National Party to retreat further south. Three more provinces—Suiyuan, Shansi, and Shantung—were controlled by Japan. Yet, the Nationalist Army, which was the official party of China, did not fight against the Japanese Army as Nationalist Party noticed its own military weakness compared with Japan and cared more about inner conflict with Communist Party. Its way of dealing with the Japanese invasion was to use space to trade for time. Two years later, in 1937, Japan committed a heinous crime in Nanking and moved further southward. Finally, Japan surrendered in 1945 and stopped its persecution of China. Therefore, many historians believe that the Invasion of Manchuria and the establishment of Manchukuo were the beginning of Japan's systematic invasion of China. Reference: "1899: Hong Kong in the Age of Imperialism." The Six-Day War of 1899: Hong Kong in the Age of Imperialism, by Patrick H. Hase, Hong Kong University Press, 2008, pp. 5–22. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1xwbjg.6. Accessed June 24th, 2021. Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Second Sino-Japanese War." Encyclopedia Britannica, November 10th, 2020, https://www.britannica.com/event/Second-Sino-Japanese-War. Accessed June 24th, 2021. Gates, Rustin. "Solving the 'Manchurian Problem': Uchida Yasuya and Japanese Foreign Affairs before the Second World War." Diplomacy & Statecraft, vol. 23, no. 1, Mar. 2012, pp. 23–43. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1080/09592296.2012.651959. Mutter, James. "Japanese Society and the 1931 Invasion of Manchuria." The Atlas: UBC Undergraduate Journal of World History. 2004. https://ubcatlas.files.wordpress.com/2012/04/2004-mutter.pdf Saito, Hirosi. "A Japanese View of the Manchurian Situation." The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 165, 1933, pp. 159–166. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1018175. Accessed June 24th, 2021.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

|

Pacific Atrocities Education

730 Commercial Street San Francisco, CA 94108 415-988-9889 |

Copyright © 2021 Pacific Atrocities Education.

We are a registered 501 (c)(3) charity. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>