|

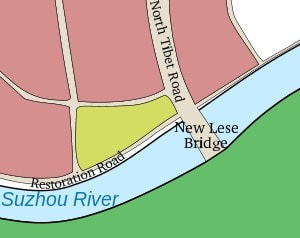

Guest post by Tim Qiu, Instagram @asianww2addict It is the fall of 1937, and the Battle of Shanghai rages on furiously. The city once known as “the Pearl of the Orient” (not to be confused with Manila, Philippines) was barely recognizable after more than three months of continuous fighting and siege. Historians often compare the intensity of this urban warfare to that of Stalingrad in 1942. It was only the beginning of a damned war doomed to last eight years. Amid the fiery chaos, a group of dauntless soldiers from the 88th Division NRA firmly and heroically stood their ground and opposed the invading Japanese for six long days. They would be immortalized today as the ‘800 heroes [of Sihang]’, and their tale is one worth to be told. Following the Marco Polo Bridge Incident of July 7, 1937, Japan invaded mainland China without declaring war. However, they reached the suburbs of Shanghai on August 13 that same year, initiating the first exchanges of fire with Chinese defenders. The Japanese were hesitant to shell or aerially bombard suspected enemy positions along the Suzhou River since one side contained foreign concessions and international settlements. The use of mustard gas and other chemical weapons was also limited, fearing of attracting foreign spectators. Situated on the riverbank, the Sihang Warehouse was consequentially mostly exempted from such attacks. But, unfortunately, this meant it had to be rooted out inch by inch, giving way to a glorious last stand by the Chinese. By October 27, the first day of the battle, the 1st Battalion of the 524th Reserve Regiment (88th Division NRA) contained 414 soldiers after the battalion was reduced to half of its initial strength due to the heavy street-to-street fighting. The Chinese forces had a numerical advantage, but their only tanks were used as infantry support, such as the German-provided Panzer I’s. Japanese ones outgunned them, forcing the Chinese to withdraw on several occasions after taking an objective. They sometimes had to resort to suicide-bomber tactics, sacrificing their own lives to save their fellow soldiers potentially. Chinese soldiers would strap satchel charges (a bundle of grenades in a sack) to their bodies and dive under moving enemy tanks to detonate their explosives and destroy/disable the tank. The Japanese also used this concept in the later stages of the war in the Pacific. They had more extensive variations such as the Kamikaze Corps, underwater frogmen, aerial ramming, etc. As mentioned previously, the 1st Battalion only had 414 combat-effective soldiers. So why were they named the ‘800 Heroes’? In short, they wanted to show no weakness and, following the principles of Sun Tzu in the Art of War, appeared strong when they were weak. They did not reveal the actual numbers and told the media that they were 800 men ready to fight to the death. At around 1pm on October 27, a small-scale Japanese offensive on the warehouse was suppressed with machine-gun fire and German-provided grenades. The first day was relatively successful, but the Chinese knew they couldn’t hold on to the warehouse for very long. So they were ordered to stay put and stall the Japanese advance into Shanghai while other units retreated while putting on a show for the foreigners across Suzhou creek. Unrested and sleep-deprived, the 1st Battalion was greeted with the droning of Japanese bombers overhead and cannon fire the next day. The attackers also launched another offensive in the rain but were silent once again by well-positioned enemy fortifications. After news of the defense of Sihang reached locals across Suzhou, they joined in the fight by donating vital supplies such as food and clothing (10 truckloads in total). They were also filmed holding billboards with the approximate number of enemies and the direction from which they were coming. The Chinese were also gifted a flag of the Republic of China to erect atop the building, which they did during the early hours of the 29th. This proved to be a significant morale-raiser, for the next day, around 30,000 civilians gathered on the bank of the Suzhou Creek to show their support. Shouts of “long live the Republic of China!” could be heard from afar, but the celebration was interrupted when the fuming Japanese sent fighter planes to shoot the flag down. They were repelled and soon gave up after many unsuccessful strafing rounds, fearing to hit accidentally. A massive assault on the warehouse was launched yet again that day, and the Japanese began chipping away at the West Wall with explosives, hoping to penetrate the thick concrete barricades that resisted siege for so long. Unfortunately for them, a determined and battle-worn Chinese private strapped himself with grenades and jumped off the building into the crowd of Japanese, bringing down 20 enemy soldiers with him. After nearly an entire day of fierce fighting, the attack finally ceased as the Japanese withdrew under a smoke-filled night sky. By October 30, the Japanese had finally learned from their previous mistakes and resorted to shelling the defenders into submission. Even though the constant boom of explosions near deafened the Chinese, its actual effectiveness was very limited. Foreign troops stationed in the area were getting tired of constantly taking deviated fire and pressured the Chinese high command to make a tactical retreat out of the Sihang. A ceasefire was reached for the Chinese to pull back from the warehouse during the night of November 1 via the New Lese Bridge. During the withdrawal, Japanese machine gun nests and artillery suddenly opened up on the bridge. This was the last straw for the foreign soldiers who have been watching over the battle without being able to take any action. They responded with machine-gun fire of their own and covered the Chinese as they ran across the bridge. Around 370 soldiers safely made it to the foreign concessions on the other side, only to be placed in POW camps (as part of the agreement with the Japanese for their “ceasefire”). The Imperial Army suffered more than 200 killed taking the warehouse: an impressive feat considering their overwhelming manpower and equipment. After the Battle of Shanghai, most of China’s elite troops were depleted, and the survivors retreated to the capital city of Nanking. There, the Japanese would “avenge” their fallen comrades with an orgy of rape and sadistic slaughter of 300,000 civilians, known as the infamous Rape of Nanking. __ Sources: __ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Defense_of_Sihang_Warehouse https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Shanghai https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/2016/10/11/chinese-alamo-last-stand-at-sihang-warehouse/ https://www.warhistoryonline.com/guest-bloggers/shanghais-last-stand-800-heroes-sihang-warehouse.html https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/937493.shtml https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1198864.shtml https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_Special_Attack_Units To read more on the topic:

1 Comment

Robert Hammond

6/3/2024 09:26:17 pm

Dear Sir:

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

|

Pacific Atrocities Education

730 Commercial Street San Francisco, CA 94108 415-988-9889 |

Copyright © 2021 Pacific Atrocities Education.

We are a registered 501 (c)(3) charity. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>