|

by Tori Borges Before the conflict broke out in the Pacific, there were warning signs of trouble to come during the interwar period. As Japan made territorial gains, there were concerns from Western powers that war could break out again, especially regarding China. The 9 Power Treaty was meant to alleviate these concerns by having the world powers agree to recognize China's sovereignty and support its stability. The real motivations, however, were to protect the economic interests of Western nations. Perhaps because of this, the treaty made no overarching changes to support China against Japanese aggression and ultimately failed. The first World War left many unresolved issues that threatened another war. Though other areas in the world also threatened peace, Japan's imperial takeover and heightened militarism combined with participation in a naval arms race drew attention (U.S. Department of State). There was also concern over the fate of China and the impact of Japan's growing influence in the Pacific on Chinese trade and, by extension, the economies of Western nations. America based its foreign policy on the open-door policy, which was the idea that China's economy should be open to all countries, recognizing it as a sovereign territory (Brittanica). Japan's rising influence in the Pacific may have been of genuine concern, but there were also more selfish economic motivations from countries advocating for emphasized Chinese sovereignty. America led the charge in addressing these concerns. During the interwar period, their foreign policy towards Asia was partly informed by Stanley Hornbeck, one of the top authorities on policies for Asia of all United States Statesmen (Lehmann, 127). Hornbeck was a proponent of the Open Door Policy and emphasized the need for Chinese sovereignty. In his book Contemporary Politics in the Far East, Hornbeck recognizes America's heavy-handed role in Chinese affairs, saying it is both a business and moral duty (Hornbeck, 387). Hornbeck was also present as an American advisor at the Washington Naval Conference, where the 9-Power Treaty was signed. He was assigned to 'Pacific and Far Eastern questions' in the American Advising Committee. His advice and reports helped shape the treaties made at the conference (U.S. Department of State). Though he had extensive insight into the Far East, Hornbeck represented the interests of the United States, so his advice reflected their desire to maintain trade relations. The Washington Naval Conference's purpose was to convene the world's most powerful naval powers in Washington, D.C., to discuss interwar concerns. As a result, multiple treaties and agreements were enacted involving different nations. The three major agreements signed included the Three-Power Treaty, the Four-Power Treaty, and the Nine-Power treaty, all finalized by January 1922 (U.S. Department of State). The Nine Power Treaty specifically addressed China, while the others were more concerned with diplomacy and naval disarmament. The countries that agreed to the treaty were the United States, Japan, China, France, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Portugal (U.S. Department of State). The 9 Power Treaty potentially held implications for the fate of the Pacific, but only two powers from the region were present. The Nine-Power Treaty upheld the Open Door policy that America had followed for years but expanded it to the rest of the world powers. Those who signed the treaty agreed to recognize Chinese sovereignty and independence (The Avalon Project). Such sovereignty would keep China from becoming colonized by other powers who were looking into Asia. Moreover, because of this, there would be equal access to trade, with no country getting priority or a specific sphere of influence. Another main part of the treaty was a commitment to encourage Chinese stability (The Avalon Project). However, encouraging stability may have been less for the livelihood of the Chinese and more for the stability of markets. Another key aspect was that if there were any suspected violations, the treaty signers would meet to discuss the issue (The Avalon Project). Though in concept, this treaty looked to maintain Chinese sovereignty and prevent war from breaking out, without a proper way to ensure compliance, it was destined to be ineffective.

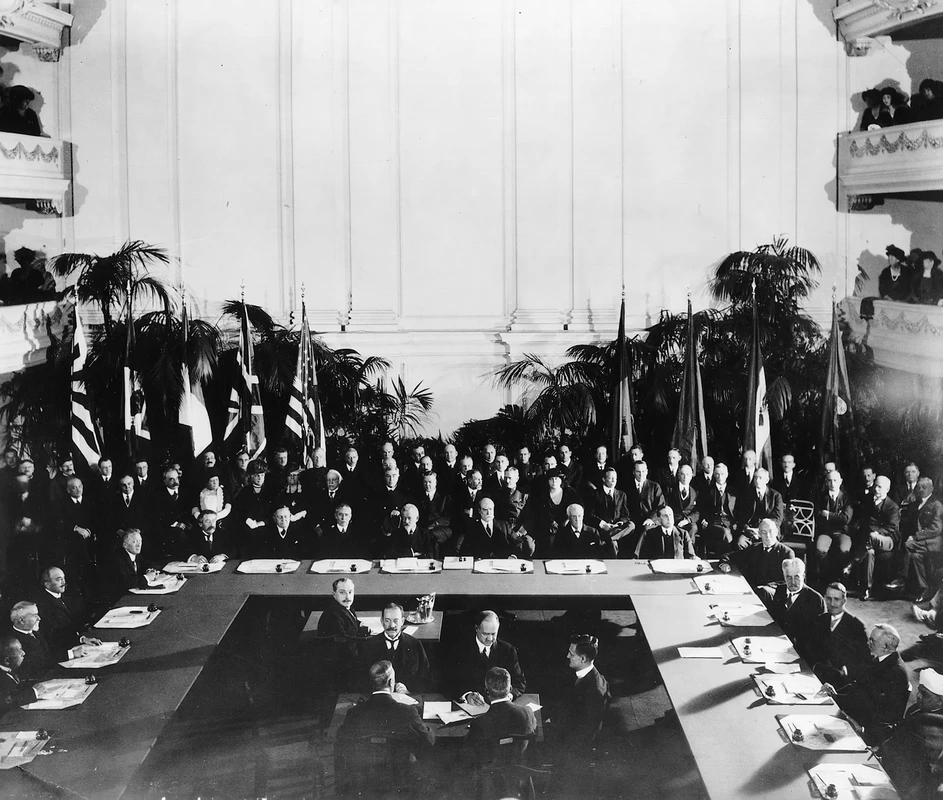

The Nine-Power Treaty was tested by Japanese aggression and failed. In 1931, Japan invaded Manchuria, and in 1937, war broke out between Japan and China. Both are undoubtedly acts of aggression and violate several terms of the treaty. However, per the treaty's terms, no tangible action was taken besides issuing protests and imposing economic sanctions. Though the invasion of Manchuria was recognized as a violation, no collective action was taken, only individual condemnation and refusal to recognize Japan's territorial holds (Japanese Conquest of Manchuria). Such a strategy failed, and in 1937 Japan further occupied China. The Brussels Conference was held to address the conflict, but Japan refused to attend, making any conversation unproductive (Hyperwar: Peace and War). Again, the Nine-Power Treaty proved ineffective, leaving it up to individual countries to address the issues. The United States attempted to punish Japan with embargos during the 1930s as tensions rose, but that ultimately did nothing to prevent World War II in the Pacific. The 9 Powers Treaty was an attempt to prevent war in the Pacific while catering to the economic needs of Western nations. Though well-intentioned, the treaty was flawed in being too resistant to provide legitimate safeguards to China's sovereignty. As a result, disarmament failed to ameliorate tensions, as did a treaty with no actual punishments or consequences guidelines. As a result, the Chinese and the rest of the Pacific bore the brunt of its failure. References "Foreign Relations of the United States : Treaty between the United States of America, Belgium, the British Empire, China, France, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, and Portugal. Signed at Washington February 6, 1922." The Avalon Project - Documents in Law, History and Diplomacy, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/tr22-01.asp. Accessed 27 July 2022. "PAPERS RELATING TO THE FOREIGN RELATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES, 1922, VOLUME I." U.S. Department of State, U.S. Department of State, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1922v01/d88. Accessed 27 July 2022. Hornbeck, Stanley. Contemporary Politics in the Far East. D. Appleton and Company, 1916. pp 387. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=JvtJAAAAMAAJ&pg=GBS.PA387&hl=en "Hyperwar: Peace and War: United States Foreign Policy, 1931-1941 (Chapter 7]." Ibiblio, https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/Dip/PaW/PaW-7.html. Accessed 27 July 2022. "Japanese Conquest of Manchuria 1931-1932." Mount Holyoke College, https://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/WorldWar2/manchuria.htm. Accessed 27 July 2022. Lehmann, Timothy C. "Keeping Friends Close and Enemies Closer: Classical Realist Statecraft and Economic Exchange in U.S. Interwar Strategy." Security Studies, 18:1, 2009, pp. 115 — 147. Accessed 27 July 2022. "Milestones: 1921–1936." U.S. Department of State, U.S. Department of State, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1921-1936/naval-conference. Accessed 27 July 2022. "Open Door Policy." Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/event/Open-Door-policy. Accessed 27 July 2022. Images "Washington Naval Conference in Washington D.C.," 1921. Photograph. Brittanica, https://www.britannica.com/event/Washington-Conference-1921-1922#/media/1/636484/95891 "United States Delegates at the Brussels Conference, Stanley Hornbeck far left," 1937. Photograph. Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Will_represent_U.S._at_nine_power_treaty_conference_in_Brussels._Washington,_D.C.,_Oct._18._The_United_States_Delegates_to_the_Conference_of_Nine-Power_Treaty_Signatories_(...)_Brussels_held_LCCN2016872457.tif

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

|

Pacific Atrocities Education

730 Commercial Street San Francisco, CA 94108 415-988-9889 |

Copyright © 2021 Pacific Atrocities Education.

We are a registered 501 (c)(3) charity. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>