|

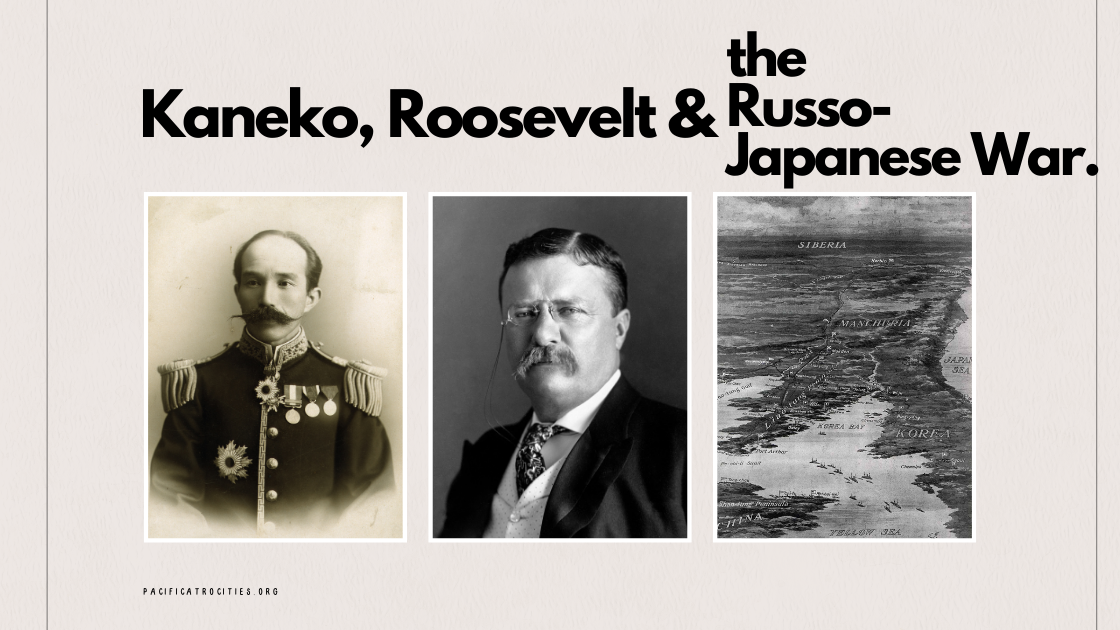

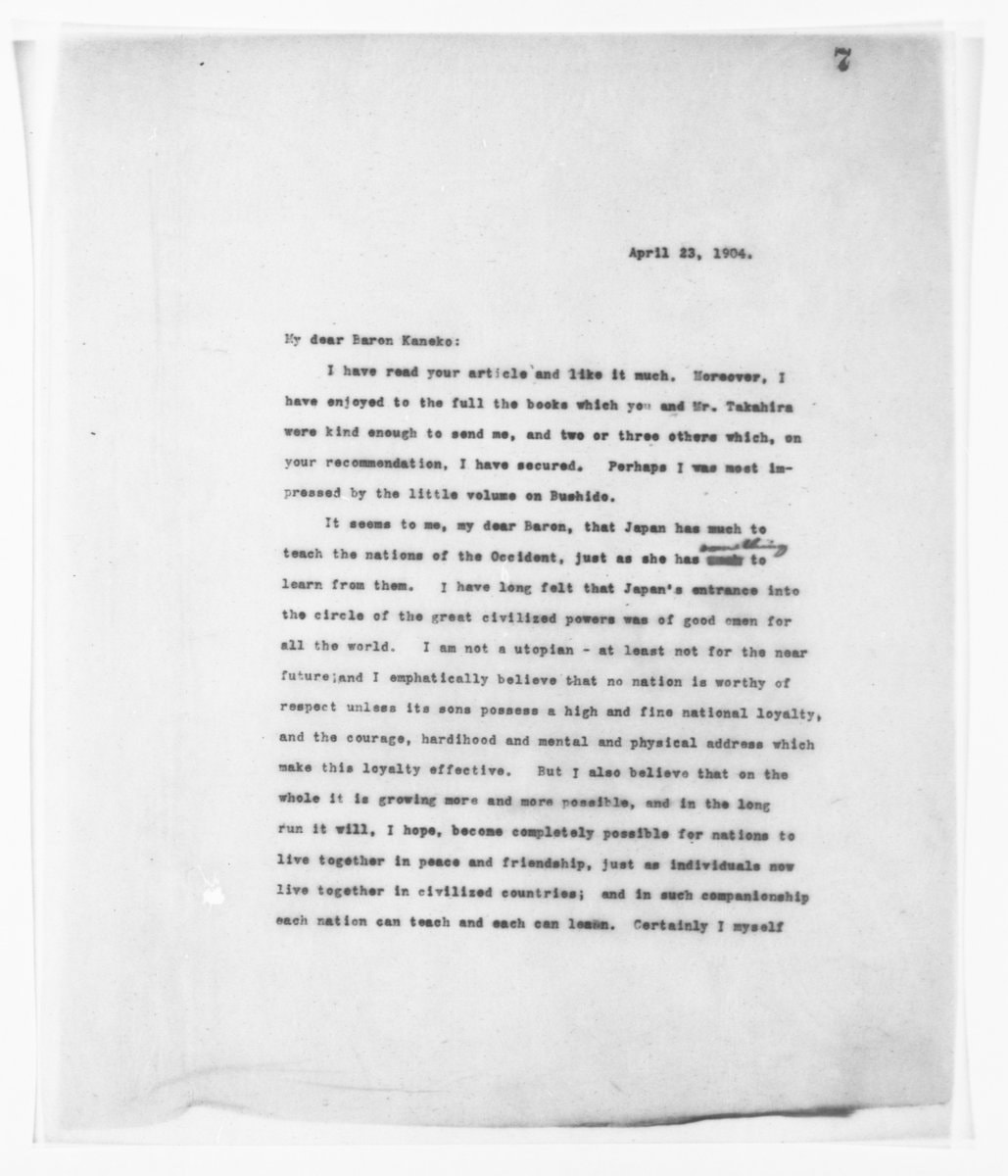

by Jolin Chan At the turn of the 20th century, Japanese and Russian imperial interests came head to head, as both were interested in expanding into Manchuria and Korea. This conflict, however, went beyond East Asia. With Western involvement, the Russo-Japanese War can be considered “World War Zero.”[1] It was a global conflict that set the stage for future world wars that intertwined the world. In the years leading up to the Russo-Japanese War, France was allied with Russia, and Great Britain was allied with Japan. The remaining were Germany and the United States. However, with the former’s past involvement in the Triple Intervention and the subsequent demand for Japan to return the Liaotung Peninsula to China, Japan turned to the United States for support. Specifically, in 1904, the President of the Privy Council, Itō Hirobumi, sent Japanese diplomat Baron Kaneko Kentarō to the United States to help cultivate friendly relations.[2] Kaneko was the perfect man for the job. He graduated from Harvard Law School’s class of 1888 and already had close contacts in America, including Theodore Roosevelt, whom he met in 1890 through a mutual Harvard friend. Kaneko’s understanding and adoption of American culture helped them become acquainted, and they remained in touch even after Kaneko returned to Japan.[3] Thus, Itō ordered Kaneko: “Only President Roosevelt of the United States can stand impartially between Russia and Japan and advise them about achieving peace. As we know that you have previously been on intimate terms with the President, we want you to go immediately and meet him and tell him this privately, and also do your best to arouse the sympathies of the American people for Japan.”[4] Though Yellow Peril sentiments were widespread and ever-growing, Kaneko was quickly welcomed back to America, especially by President Roosevelt. He arrived in March of 1904, a month into the Russo-Japanese War. In Washington, D.C., President Roosevelt invited Kaneko to the White House, treated him to luncheons and dinners, and even introduced Kaneko to his family and invited him to their vacations.[5] In return, the Japanese diplomat shared his culture with Roosevelt, recommending books such as Bushido: The Soul of Japan to the President. In his letter praising Bushido, Roosevelt also wrote: “It seems to me, my dear Baron, that Japan has much to teach the nations of the Occident, just as she has something to learn from them. I have long felt that Japan’s entrance into the circle of the great civilized powers was of good omen for the world… Certainly I myself hope that I have learned not a little from what I have read of the fine Samurai spirit, and from the way in which that spirit has been and is being transformed to meet the needs of modern life.”[6] Roosevelt’s comment on Japan joining “the circle of great civilized powers” was correct—and critical for the Russo-Japanese War. Starting in the 1850s and 1860s, the arrival of American Commodore Matthew C. Perry and the subsequent Meiji Restoration allowed the country to modernize and Westernize. Japan, no longer feudal nor isolationist, opened up to the world, letting in trade, new ideas, technology, and culture. The Russo-Japanese War became a test of the success of their modernization, and winning the war would tell the other “great civilized powers” that Japan was on its rise. Of course, simply modernizing was not enough for victory. Just as Japan had looked to the Western world for inspiration to improve its military and make scientific advancements, Japan did the same when it came to financial and public support during the war. With Roosevelt on its side, Japan was even better positioned than before to win the Russo-Japanese War. After reading another one of Kaneko’s suggestions, Roosevelt wrote to him: “I was able to understand the organization of the Japanese army and navy, and the mentality of their officers and men in detail, and in the aforesaid war situation I became firmly convinced that your country will ultimately gain victory.”[7] The close friendship that Kaneko cultivated with Roosevelt was beneficial to Japan. Not only was Roosevelt beginning to side with Japan, but his meetings with Kaneko allowed the Japanese diplomat to relay information back to Ito and Emperor Meiji, as they were awaiting his telegrams sent in code.[8] In the United States, Kaneko was strategic. He, after all, was sent on a mission that would determine Japan’s fate and global standing. Introducing Japanese culture to Roosevelt was one strategy. Another was utilizing his connections as a Harvard graduate, appealing to Harvard Clubs across the country—a piece of advice he received from the President.[9] Kaneko began touring the United States, speaking with powerful congressmen, senators, and financiers.[10] To his audience, he sold them the story that Japan was grateful for America’s help with Westernization. In return, Japan wanted to help America Westernize the rest of Asia.[11] At Sanders Theatre in Harvard, Kaneko spoke to the audience about topics that ranged from Christianity to Yellow Peril to Westernization: “Now, after having thus adopted Western civilization and assimilated our manners and customs to those of the most advanced nations, we felt it our duty to do our utmost to extend these blessings to other oriental nations whom we could influence… Japan is really acting as the pioneer of Anglo-American civilization in the East. It is for this which we are fighting, and only this which is the meaning of the war.”[12] His work paid off. Banks sold millions of dollars of Japanese bonds, and Harvard Clubs helped spread the word by distributing printed copies of his speeches.[13] Furthermore, Japan was winning the war—and Roosevelt was happy as well.[14] Ultimately, in May 1905, Ito invited Roosevelt to negotiate the end of the war with Russia and Japan. In the months leading up to the negotiations, the President met with Kaneko to discuss his thoughts on the future of Japan, saying that he believed in creating a “Japanese Monroe Doctrine” and would “support [Japan] with all [his] power.”[15] In September, representatives of Japan and Russia met with Roosevelt to sign the Treaty of Portsmouth in New Hampshire, which would later win the President a Nobel Peace Prize. The treaty recognized Japanese supremacy in Korea, and it gave the Liaotung Peninsula, the South Manchurian Railway, and the southern part of Sakhalin Island to Japan. Ultimately, Japan’s victory and new gains illustrated that the country was a rising global power that should not be underestimated. The story of Kaneko, Roosevelt, and the Russo-Japanese War is a story of diplomacy and connections that cross borders, and it reveals a lesser-known narrative of Japan-United States relations, which would drastically change as the twentieth century went on. The interconnectedness of these countries helped build the foundation for the world wars that would be fought in the coming decades and enveloped even more of the globe in conflict. Sources: 1. The Russo-Japanese War and World History, 19 2. Baron Kaneko and the Russo-Japanese War, 7-8 3. TCM, 60. 4. Baron Kaneko and the Russo-Japanese War, 8 5. TCM, 67. 6. Letter from Theodore Roosevelt to Kentarō Kaneko. Theodore Roosevelt Papers. Library of Congress Manuscript Division. https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Research/Digital-Library/Record?libID=o187994. Theodore Roosevelt Digital Library. Dickinson State University. 7. Baron Kaneko and the Russo-Japanese War, 55 8. TCM, 67. 9. Baron Kaneko and the Russo-Japanese War, 53 10. TCM, 68. 11. TCM, 69. 12. Baron Kaneko and the Russo-Japanese War, 92 13. TCM, 69 14. TCM, 71. 15. TCM, 74.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

|

Pacific Atrocities Education

730 Commercial Street San Francisco, CA 94108 415-988-9889 |

Copyright © 2021 Pacific Atrocities Education.

We are a registered 501 (c)(3) charity. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>