|

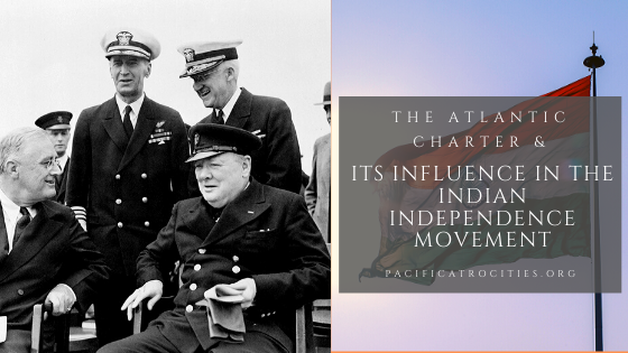

by Rubayya Tasneem An essay on the Atlantic Charter and its influence on the Indian independence movement. Amidst the intense fighting in 1941, with the Second World War in full swing, the allied forces had suffered humiliating defeats at the hands of the German troops, and few policymakers believed that the Soviet Union would be successful in defending the 1941 invasion. To ensure victory, Churchill was of the opinion that US involvement in the war was crucial, leading to the meeting between Roosevelt and Churchill aboard the SS Augusta in August 1941. Britain, who was desperately in need of US support, decided to clarify their war aims in order to amass US support, ultimately resulting in the Atlantic Charter. The Atlantic Charter was not binding on either party, but it still proved successful in affirming the solidarity between the US and Britain against Axis aggression and laid out Roosevelt’s vision for the postwar world characterized by a free exchange of trade, self-determination, and collective security. The joint declaration by US President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill on August 14, 1941, stated that “two leaders (Churchill and Roosevelt) deem it right to make known certain common principles in the national policies of their respective countries on which they base their hopes for a better future for the world.” This was a monumental agreement, paving the way for the establishment of the United Nations, influencing policymaking at the global level for generations to come. But the Charter had ramifications for the independence movement in India, as a key provision of the Charter conferred the right of self-determination for countries across the globe, which should have, by definition, included the British colonies. This condition was imposed by the then American President Roosevelt, who, when approached by Churchill, stated that the benefits of the Charter, especially that of self-determination, should extend to its colonies, as well as the war-torn European countries. During Britain’s imperial reign, India was popularly referred to as the ‘jewel in the crown of the British Empire,’ but against the backdrop of the Second World War as well as the Atlantic Charter, Britain had to contend with the political and religious upheavals undergoing in India. Another important development in India was the involvement of Subhash Chandra Bose, one of the most prominent Indian leaders at that time, in promoting the Axis powers, as well as urging Indians to rely on Axis arms for their emancipation from imperialist rule. This was very similar to the political strategy utilized by Tokyo at that time, which involved appealing to the colonized people of Asia as their liberator from imperial rule. Thousands of native nationalists in Burma, inspired by the Japanese rhetoric, had subsequently helped the Japanese oust the British. Exacerbating this situation was the fact that Bengal, where Bose’s influence was the strongest, was also the region lying first in the path of the Japanese advance. Therefore, Britain was forced to reassess as these political considerations transformed into military ones with dire consequences. It was evident in this case that the Viceroy and his councils could not aspire to mobilize the masses required in order to fight the invasion. Only the Indian nationalist movement, whose presence was pervasive, was capable of this task. As the invasion became imminent, it was necessary that a change in their approach was required, and even the British public opinion began to insist on it, leading to the Cripps mission, first in the many that would follow, which became instrumental in India’s independence. The British army that resulted consisted of Indian soldiers who did not necessarily prioritize the British values, nor sympathize with their cause. This was, in essence, an army that was not fully indoctrinated, and easily switched sides to the cause of Subhas Chandra Bose (in his Delhi Chalo mission). The few percents of the Indian soldiers who changed sides were subsequently put on trial in the Red Fort, leading to unrest in the army. These trials attracted publicity, and the outcry over these trials even forced the then Army Chief Field Marshal Claude Auchinleck to commute the sentences of the three defendants in the first trials. The fact that these trials garnered much public sympathy, and taking into account the concurrent protests and non-cooperation movements, the support within the British army faltered. This was accompanied by the mutiny in the Indian Royal Navy. The reality of these wavering support, accompanied by NCOs in the British Indian Army ignoring orders from their superiors, forced the British to reassess their relationship with India. These events led to the conclusion that sustaining a military presence in India, consisting of Indians, was not viable for the British. The British, already exhausted by the war, realized that they could not depend upon the loyalty of the Sepoys, and ultimately made the decision to quit its colony. All things considered, despite being on the victorious side of the Second World War, it may be said that Britain had little to boast. Its economy, prestige, and authority were shaken, and as soon as the war ended, it was evident that Britain no longer possessed the authority to defeat another mass uprising by India. Thus, granting freedom to the jewel in the crown, as they so eloquently described India, became a necessity after the war. References https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/atlantic-charter https://swarajyamag.com/blogs/how-churchills-denial-of-the-atlantic-charter-rewards-to-india-pitted-him-against-roosevelt Related Books

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

|

Pacific Atrocities Education

730 Commercial Street San Francisco, CA 94108 415-988-9889 |

Copyright © 2021 Pacific Atrocities Education.

We are a registered 501 (c)(3) charity. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>