|

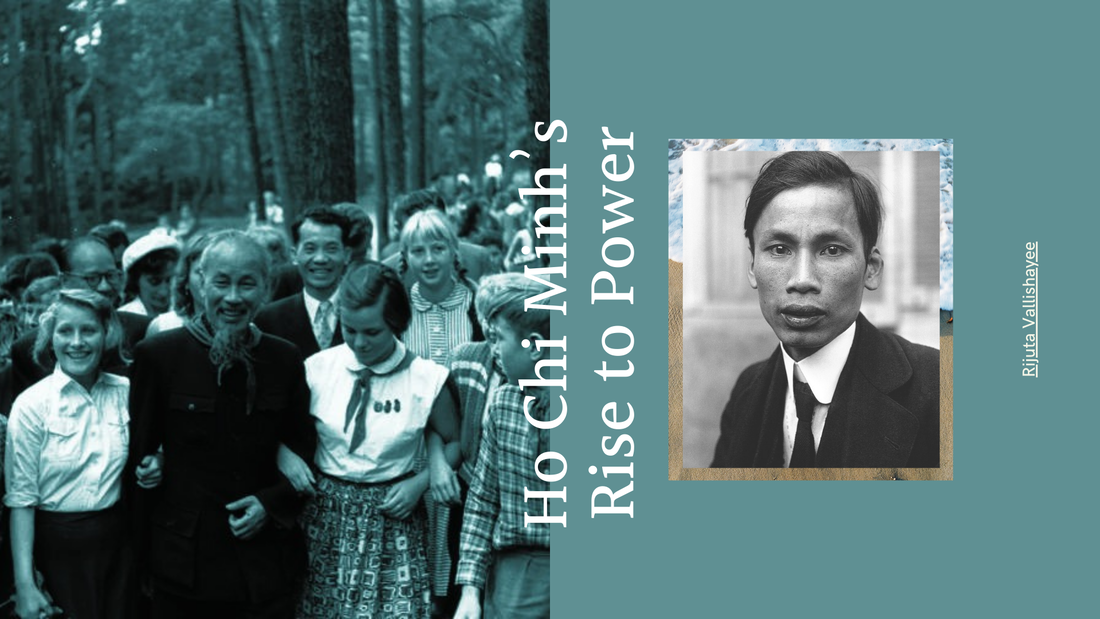

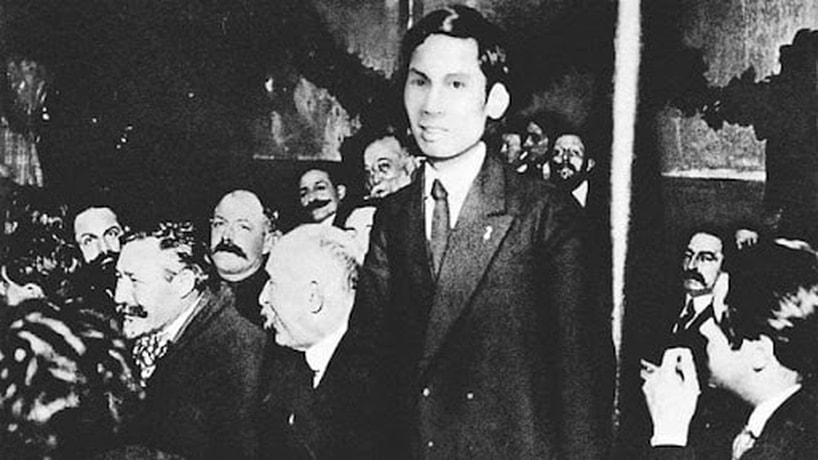

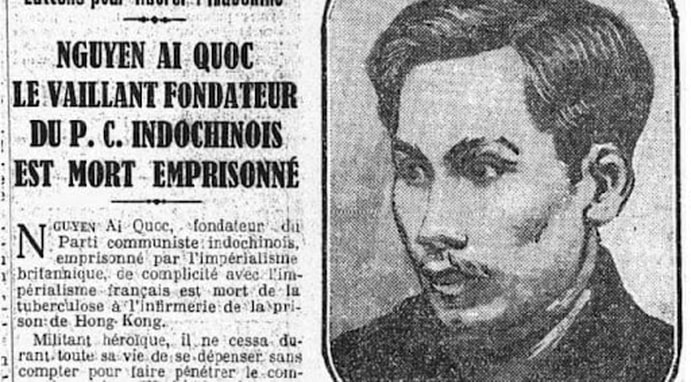

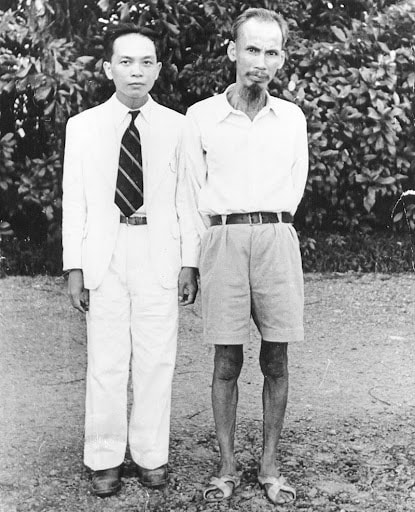

by Rijuta Vallishayee Alternately revered and condemned across the world, Ho Chi Minh was one of the more enigmatic world leaders who emerged from the ashes of the Second World War. His early life and his rise to power remain shadowy, perhaps due to his usage of multiple aliases and general lack of reliable sources for his life before he came to power in 1945. Nevertheless, the available details reveal an intriguing life defined by the events of the first half of the twentieth century and a great love for his country. Understanding Ho’s rise to power is essential to understanding how Vietnamese independence was achieved and maintained throughout the twentieth century. Ho Chi Minh was born as Nguyen Sinh Cung in 1890, to the Confucian scholars Nguyen Sinh Sac and Hoang Thi Loan in the province of Nghe An in Annam, French Indochina. At the age of eleven, Nguyen Sinh Cung’s parents changed his name to Nguyen Tat Thanh (Duiker chapter 1). His education was scattered across Vietnam as his father moved from the imperial court at Hue to various other cities in Vietnam. Despite this, he learned classical Chinese, quoc ngu, and French. Ho’s studies came to an end when he was caught interpreting for Vietnamese demonstrators in Hue, leading to his expulsion in 1908. After three years of working as a teacher, he decided to travel abroad (Pike 13). Going by the name of Ba, he traveled as a messboy on a steamship to France. Whether Ho chose to travel out of dissatisfaction with his life in Vietnam or in order to “know thy enemy,” the decision would have a profound impact on his political identity and the course of Vietnamese history. Ho traveled from port to port, witnessing the oppression of the people of French colonial Africa and Black people in the United States (Duiker chapter 2, Ho 20). Eventually, he settled in England for four years, where he became involved with labor unions such as the Overseas Workers’ Association (Duiker chapter 2). It is likely that England was where he first began his involvement with leftist causes (Pike 14). Ho continued his commitment to such causes when he returned to France in 1917 and immediately got involved with Vietnamese anticolonial groups and the French Socialist Party. As the victorious Allied powers gathered in Versailles to negotiate a treaty to end the First World War, Ho wrote his “Revendications du Peuple Annamite,” an eight-point paper that declared political autonomy and civil and labor rights for the Vietnamese (Duiker Chapter 2). He signed it with the name Nguyen Ai Quoc, a pseudonym meaning “Nguyen the Patriot.” Although the petition did not gain official recognition, it sparked the French police force’s interest in him. The event gained him notoriety in both French, Vietnamese, and leftist circles, as Ho grew more and more involved in the French Socialist Party’s activities (Duiker chapter 2). When the party split over the Third Communist International (Comintern), Ho joined the French Communist Party. It is likely that Leninist support for nationalist causes in the colonies was what first drew Ho to Marxism-Leninism. Ho’s piece “Some Considerations on the Colonial Question,” published in L’Humanite in 1922, reveals Ho’s frustration towards the French brand of colonialism, entreating the French party to intense propaganda in the region (Ho 17). This piece, as well as Ho’s relatively late exposure to Marxist-Leninist ideology, indicate that Ho primarily viewed Marxism-Leninism as a framework for nationalist revolution. In 1924, Ho, still using the name Nguyen Ai Quoc, traveled to the USSR and joined the Far Eastern Bureau, as well as began attending courses at the University for the Toilers of the East (Duiker chapter 3). Here, Ho gained experience as a professional revolutionary and participated in the Fifth Comintern. His speeches highlighted the importance of the peasantry as a revolutionary factor, which differed from the more orthodox focus on the proletariat (Ho 1924 in Lacouture 45). However, his understanding of the peasantry as a proletariat in a primarily agrarian country would prove crucial to Vietnam’s approach to warfare in the latter half of the twentieth century. Eventually, Ho’s revolutionary experience granted him a position as a Comintern representative to the Kuomintang (KMT) revolutionary government in Guangzhou, China. Upon his return to Asia after thirteen years, Ho went by the pseudonym Ly Thuy in order to avoid the authorities as he worked to transform the Vietnamese nationalist groups in Guangzhou into more progressive organizations (Duiker chapter 4). It was here that Ho co-founded the Association of Vietnamese Revolutionary Youth, the organization which would serve as the seed for the Indochinese Communist Party (Lacouture 10). He trained would-be Vietnamese revolutionaries, who returned to Indochina and began to build a network of organizations to further their cause. However, as Chiang Kai-shek began purging leftists from Guangzhou, Ho traveled to Siam (Thailand) to avoid arrest. In his absence, the Revolutionary Youth League had fractured into smaller parties. In 1930, Ho returned to Hong Kong and presided as the official Comintern representative over the consolidation of these parties into the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP) (Duiker chapter 5). Soon after, due to a leak in the organization, Ho and many other ICP leaders were arrested by the British (Lacouture 63). After he was arrested, Nguyen Ai Quoc, as he was still known to Moscow, allegedly died in a Hong Kong Prison (Lacouture 64). This faked death contributed significantly to the mystery surrounding the rise of Ho Chi Minh, as few outside authorities would not realize that Ho Chi Minh was none other than the veteran revolutionary Nguyen Ai Quoc until after 1945. Instead, Ho managed to escape Hong Kong, and after lying low for half a year, he returned to China in Shanghai and connected with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), where he served as a health inspector, journalist, and troop inspector at Guilin, Hengyang, and Chongqing. From Chongqing, Ho was able to get in touch with his colleagues at the ICP (Lacouture 7). Using the alias Tran, he managed to travel to Kunming and connect with many of the men who would grow prominent in the ICP and the DRV (Lacouture 71). Secretly returning to Vietnam in 1941 for the first time in thirty years, Ho set up headquarters in mountainous Pac Bo (Duiker chapter 8). There, Ho set up the League for Vietnamese Independence (Viet Minh), forgoing the international, Third Comintern style of internationalism for a nationalist front that focused on the peasantry (Ho 29). The goal of the Viet Minh was national independence, with a focus on helping the Communist Party gain power after independence was achieved. Ho remained the driving force behind the Viet Minh’s activities as they sought to carve out a liberated base area and wage a “people’s war” in the Maoist fashion. As the Second World War raged in Europe and East Asia, Ho decided to return to China in 1942 to gain the KMT’s support for the Viet Minh. This time, Ho used the name Ho Chi Minh, using the character from his previous Chinese surname to ensure that his Chinese colleagues knew he was the same person as Hu Guang (Lacouture 78). However, he was called “Uncle Ho,” displaying the degree of reverence, admiration, and respect held by his comrades. Ho’s activities during the Second World War are especially crucial to understanding his rise to power. In four years, Ho went from the leader of the infant Viet Minh to the man who declared Vietnamese independence in August 1945. Although the time frame in which Ho Chi Minh came to power was short, the base of knowledge and support he built in his previous incarnations were crucial to understanding both Ho’s personal rise and the ascendancy of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam The base of support Ho built was especially crucial since Ho spent much of the remainder of the Second World War in China. When he was imprisoned by the KMT in 1942, the Viet Minh immediately took action, sending operatives to China to obtain his release (Duiker chapter 9). Eventually, the general responsible for his imprisonment, Zhang Fakui, released him and decided to use Ho to revitalize his own Vietnamese nationalist organization, the Dong Minh Hoi. In exchange, Zhang promised Ho that he would be able to return to Vietnam, which he did in 1944 (Lacouture 83). While Ho had been in China, the war had shifted in the Allies’ favor, though the Japanese remained firmly entrenched in Indochina due to an alliance with the Vichy government. The Viet Minh had expanded throughout northern Indochina and began establishing operations in the south. The possibility of an Allied invasion of Indochina was growing, and planning for a general insurrection grew more urgent as the Viet Minh aimed to have a revolutionary government in place to negotiate with the invasive forces. When Ho returned, he agreed to his colleagues’ proposal to begin forming propaganda units for what would become the Vietnamese Liberation Army (VLA) (Lacouture 89). In 1944, Vietnam was also hit with a devastating famine, initially caused by bad weather but severely exacerbated by Japanese and French exploitation of land and peasant workers. In the midst of the famine, the Japanese launched a coup d’etat against the French and set up a puppet government headed by the last Nguyen Emperor, Bao Dai (Kiernan 380). The American armed forces began their island-hopping campaign, leading many to believe that the end of the Pacific War was at hand. With the rapid escalation of events both at home and abroad, the Viet Minh decided that the time was ripe for increasing military engagement and expanding the VLA. Therefore, when the United States armed forces dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Ho was ready to launch the Viet Minh’s general insurrection (Ho 32-33). Although the VLA was not completely equipped to match Japanese forces in Indochina, they moved southwards from the Viet Minh base near the Guangxi border towards the Red River Delta, where they were assisted by popular uprisings in the destruction of government power. Despite facing resistance from the Japanese, the revolutionary troops managed to seize power in a number of towns and cities across Tonkin. A Military Insurrection Committee infiltrated Hanoi, the northern capital, organized revolutionary cells, and successfully took the city without bloodshed in three days. In the central region known as Annam, distance from the Viet Minh base in the far north led to local party leaders taking matters into their own hands. Using pressure from the new government in Hanoi and Viet Minh cadres in the neighboring villages, the local uprising government successfully took power in the central capital of Hue. In the southern region of Cochinchina, a non-Viet Minh nationalist front had taken power in the capital of Saigon, and the regional representative of the Viet Minh managed to successfully convince the new ruling committee to ally with the Viet Minh. By the end of August, all three historic regions of Vietnam were under Viet Minh control (Duiker chapter 10). Ho arrived in the city of Hanoi to begin the formation of the first independent Vietnamese government in a century. Emperor Bao Dai abdicated his throne, and on September 2nd, 1945, the newly declared President Ho Chi Minh declared Vietnam’s independence to a crowd in Hanoi (Lacouture 110). However, the Allies had already decided to separate Indochina into two zones to facilitate Japanese surrender (Kiernan 382). Meanwhile, the French government expressed interest in returning Indochina to their colonial empire. Ho reached the zenith of his governmental power as nearly three decades of bloody conflict over the nature of the Vietnamese government began. While Ho would live to see an independent Vietnam in 1954, he died in 1969 and would not live to see Vietnam reunited after the Second Indochina War. Nevertheless, “Uncle Ho” lived on as a revered, almost mythical figure in the hearts of the Vietnamese people. From the son of Confucian scholars to a traveling socialist, from legendary Comintern operative to father of modern Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh’s rise to power truly embodies the effects of the tumultuous twentieth century. Works Cited Duiker, William J. Ho Chi Minh. First edition., Hyperion, 2000. Kiernan, Ben. Viet Nam : a History from Earliest Times to the Present. Oxford University Press, 2017. Ho, Chi Minh. Selected Articles and Speeches, 1920-1967. Edited by Jack Woddis. First edition, International Publishers, 1969. Lacouture, Jean. Ho Chi Minh: A Political Biography. Translated by Peter Wiles. First edition., Random House, 1968. Pike, Douglas. “Ho Chi Minh: A Post-War Re-Evaluation.” Vietnam Center and Sam Johnson Vietnam Archive. No Date, Box 05, Folder 13, Douglas Pike Collection: Unit 08 - Biography, Vietnam Center and Sam Johnson Vietnam Archive, Texas Tech University, https://www.vietnam.ttu.edu/virtualarchive/items.php?item=2360513065. More from Rijuta Vallishayee

2 Comments

9/1/2022 02:29:15 am

Hi Rijuta.

Reply

4/19/2023 03:59:53 am

We are offering:-

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

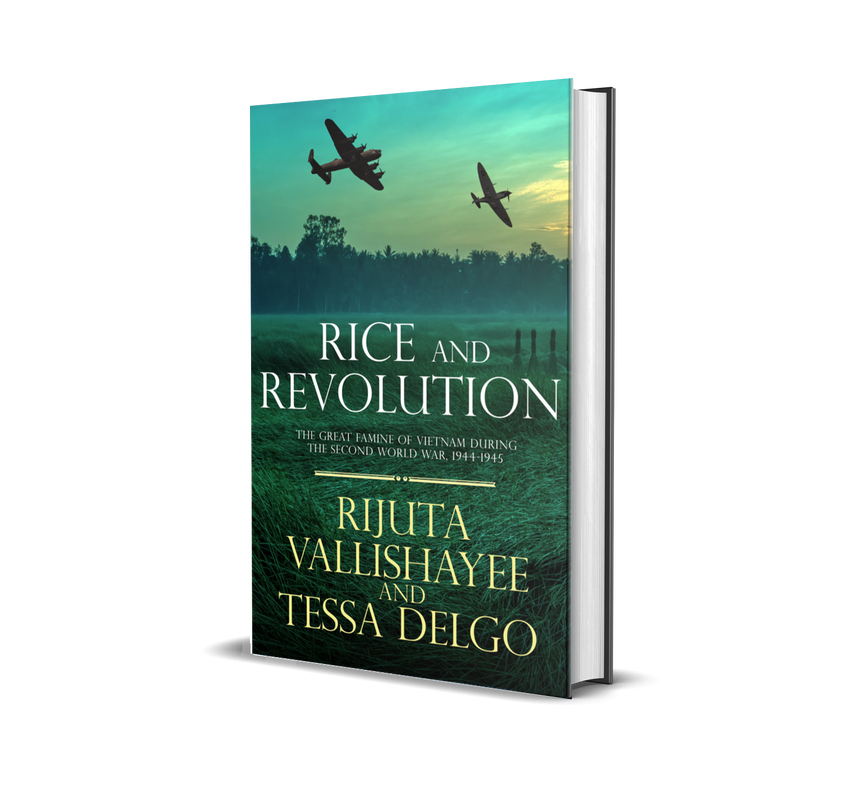

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

|

Pacific Atrocities Education

730 Commercial Street San Francisco, CA 94108 415-988-9889 |

Copyright © 2021 Pacific Atrocities Education.

We are a registered 501 (c)(3) charity. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>