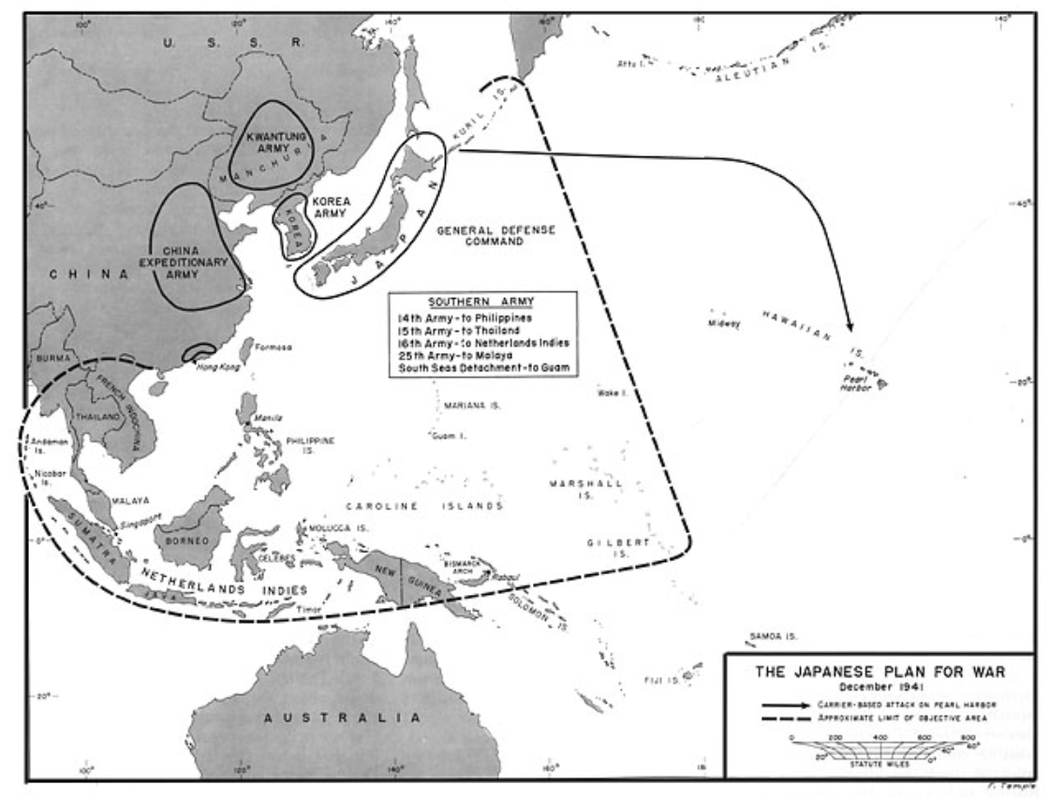

Filipina Resistance Fighters: Women’s Contributions to the Liberation of the Philippines, 1942-19459/1/2017 By: Stacey Anne Baterina Salinas The attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7th of 1941 represented the initial step of the Japanese military onslaught of Southeast Asia. The following day, the Japanese continued their aggressive military strategy in the Pacific, targeting American and European holdings in Southeast Asia. From December 8th, 1941 to May of 1942, the Japanese campaign for the Philippines resulted in both the Japanese occupation of the Philippine Islands and the ultimate surrender of both Philippine and American troops[2]. Estimates of 80,000 Filipino and American soldiers were forced to relocate and enter POW camps throughout the island of Luzon once they survived the horrors of the Bataan Death March[3]. Forced to submit to the harsh working conditions of the camps, supervised and scrutinized by Japanese draconian methods, and forced to live in squalid and poorly supplied quarters, American and Filipino troops experienced first hand the brutality of the Japanese Imperial Army. It was clear even during the initial phases of the Japanese occupation of the Philippine Islands that Japanese maltreatment of their captured adversaries had completely contradicted the official conduct of war[4]. The Japanese maltreatment of the Philippine and American POWs was visible to Philippine citizens who witnessed first hand the Bataan Death March as onlookers and passerbys. Philippine civilians who watched the brutality and killing of POWs as they marched to be transferred to the prisoner camps also were vulnerable to the cruelties of the Japanese military. Philippine men and women who attempted to give food or water to the marchers were injured or killed (bayoneted) as a result of their sympathies to the American and Philippine forces[5]. The Bataan Death March would serve as the precursor to the Japanese Imperial Military’s antagonistic treatment of the Philippine citizenry throughout the islands. The visible signs of maltreatment, the aggressive barring of civil liberties (Japanese propaganda, the torture and capture of Philippine citizens who sympathized with the Allies, etc.), and the immediate severing of foreign relations and aide would spur a Philippine grassroots movement to thwart the Japanese occupation of the Philippine Islands. The roots of the Philippine Resistance represented the cultural and socio-economic diversity of the Philippine Islands. From socialist peasant farmers, middle school teachers, ROTC youths, to Moro (Philippine Muslim) warriors, the range and inclusivity of the men and women who participated in the struggle against the Japanese Imperial Army was seemingly inexhaustible. Women guerrilla fighters especially made major contributions to the liberation of the Philippines, but unfortunately, similar to the ethnic minority guerrilla fighters, have received less acknowledgement and discussion in World War II history of the Pacific Theater. The Philippines, during the early half of the twentieth century, witnessed few advances in women’s rights. But with the threat of war and the encroachment of the Japanese Imperial Army upon the Philippine Islands, the patriarchal and religiously conservative culture of the Philippines could not afford to maintain its traditional standards of gender. The grassroots resistance drew in the patriotic fervor of many Filipinas who saw the guerrilla resistance as an opportunity to liberate their homeland as well as prove the capabilities of their sex. Their guerrilla efforts proved women were more than capable of taking on numerous roles: soldiers, leaders, activists, journalists, nurses, doctors, spies, and dedicated patriots. Filipina guerrillas proved to be a vital aspect of both the soldiering and reconnaissance missions that allowed for the Allies to gain an opportunity to retake the Philippines. Historians estimate that for every ten male guerrillas, one Filipina guerrilla served in the underground resistance[6]. Over 260,000 male Filipino guerrillas served the resistance effort[7]. This male-dominated number therefore reflects that Filipinas in wartime history have been neglected, or because of their status as women were not counted officially as serving, and that the female guerrilla populations represented possibly more than 10% of the guerrilla resistance. These statistics given the little surviving resources on Filipina guerrilla efforts brings to light the missing narratives of a traditionally very American-centered written history on the liberation of the Philippines of World War II. The war time experiences of women of color in the Pacific can provide opportunities to address the various contributions, struggles, and cultural diversity that aided and represented the Allied front of the Pacific. Filipina guerrillas similar to their male peers were aware of the risks and ultimate sacrifices they would make in their efforts to push the Japanese Imperial Army out of the Philippines. One of the added fears and risks that Filipinas shared that their male peers did not was the threat of rape and being forcibly used as comfort women (sex slaves) for the Japanese Imperial Army. Despite the risks of death, torture, and rape, the Filipina guerrillas of the Philippine Resistance represented a hardy and selfless cause of both liberation from the Japanese imperial regime and progress towards women’s rights in the Southeast Asia. Filipina guerrillas took on various roles and missions to aid the resistance against the Japanese Imperial Army. Many served as medical aides or nurses. The late Dorothy Dowlen, a Filipina mestiza (mixed ancestry of Philippine and European heritage) born and raised on Mindanao served as a medical aide helping Allied soldiers and guerrilla fighters while helping her own family escape the brutalities of the Japanese invasion[9]. Filipina nurses provided the much needed medical help for struggling American soldiers who escaped the POW camps throughout the Philippine Islands. Filipina nurses and doctors such as Bruna Calvan, Carmen Lanot, and Dr. Guedelia Pablan would continue to help civilians, soldiers, and POWs in the region surrounding Bataan despite the loss of their hospital and lack of supplies and food[10]. Risking their lives to smuggle medicine into POW camps and maintain their self-constructed health centers (nipa huts), Filipina guerrillas and female resistance supporters helped not only to physically heal the wounded but strengthened community and soldier morale to fight against the Japanese Imperial Army. Many Filipina nurses used their medical training to assist other guerrilla groups such as the WAS (Women’s Auxiliary Service), led and founded by Josefa Capistrano. Josefa Capistrano, a Chinese-Filipina mestiza would be one of the first Filipinas to establish and train women as soldiers, nurses, and spies schooling them in methods of reconnaissance and the use of firearms and self defense[12]. Capistrano’s female troops served under the tenth military district in Mindanao and would also supply the guerrillas and local communities with food, medical, and military supplies[13]. In 1963, the WAS would be renamed the WAC (Women’s Auxiliary Corps) and would become an official military branch of the Philippine Army managed by women for women[14]. Other Filipina guerrillas pursued reconnaissance missions, establishing guerrilla networks throughout the Philippine archipelago, maintaining contact with the Allied forces, and thwarting Japanese propaganda efforts (film, radio broadcasts, newspapers, pamphlets) seeking to win over the Philippine people’s support. Filipina guerrillas like Colonel Yay Panlilio served as a radio and newspaper journalist while fighting alongside, and leading her very own unit of, male guerrillas under the Markings Guerrilla troops on the island of Luzon. Panlilio used her journalist skills to skillfully hide resistance messages in public radio announcements. She also documented and maintained guerrilla activities relaying communication to the Allied forces and to other guerrilla organizations. Panlilio also routed out undercover Filipino collaborators (makapili) who sought to paint the Philippine Resistance as detrimental to Imperial Japan’s efforts in absorbing the Philippines into a “friendly” pan-Asia.[16] These courageous women broke gender norms while ultimately liberating their homeland from Japanese imperialism all the while promoting the capabilities and mastery of skillsets women were capable of in a male centered society. Through their sacrifices, Filipina resistance fighters like Josefa Capistrano championed gender and racial equality as one goal for their resistance efforts. Capistrano would not accept honorable mentions or awards for her efforts until the Philippine government recognized the WAC as an official branch of the military.[17] Most importantly, their contributions to the Pacific Theater demonstrated the many strengths of past colonial territories whom were undoubtedly deserving and capable of self governance during the post war era. References

Related ArticlesRelated Books

1 Comment

Michael Langston

7/15/2018 08:25:34 am

Much love to the brave phillipino women who

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

|

Pacific Atrocities Education

730 Commercial Street San Francisco, CA 94108 415-988-9889 |

Copyright © 2021 Pacific Atrocities Education.

We are a registered 501 (c)(3) charity. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>