|

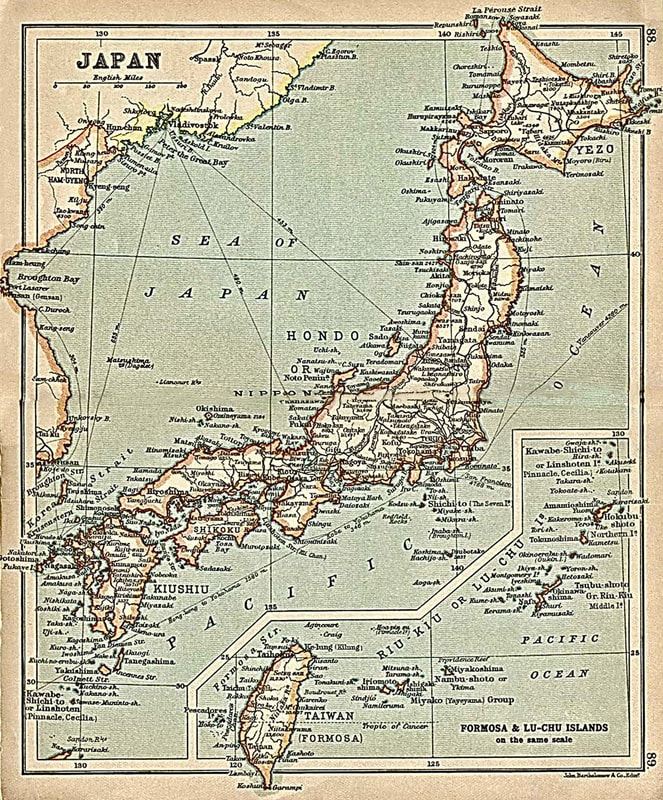

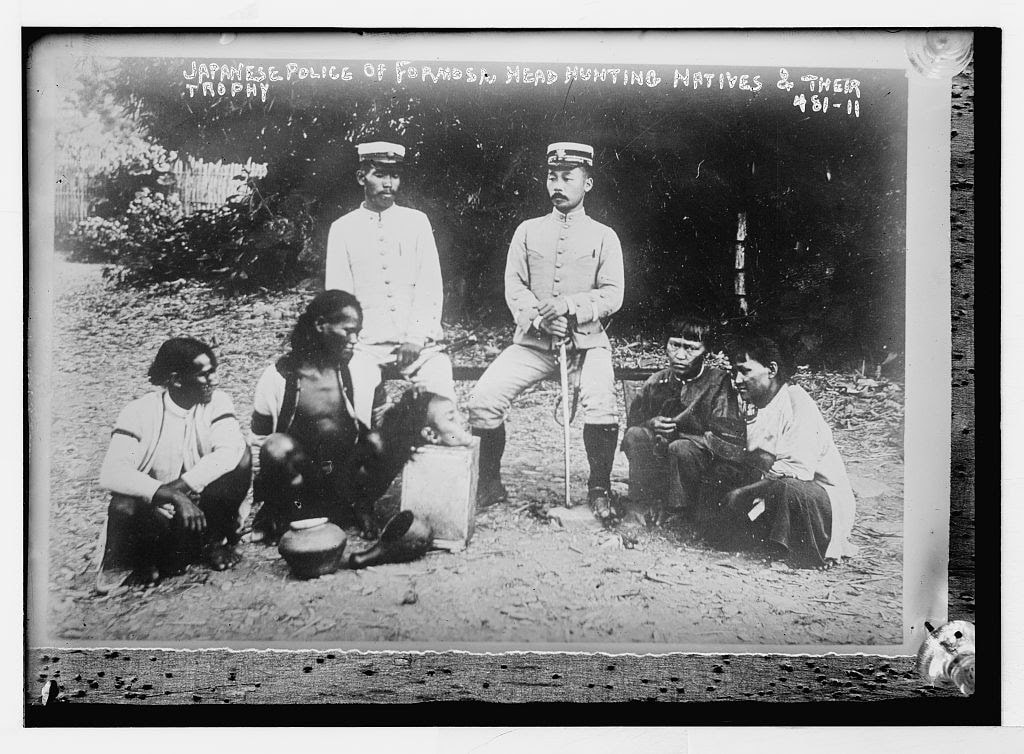

by Zoe Lee-Divito Taiwan’s history with Japan predates the Second World War, 15 years before its annexation of Korea, with an account that many Taiwanese remember to this day. Before Taiwan was under Japanese colonial rule, it was under the administration of the Qing government, who colonized the island that was inhabited by the Taiwanese indigenous people, a collective term for the variety of groups that have lived on the island for thousands of years. As early as 1683, the island was shaped by the increased migration of a Chinese population. There were settlements, uprisings, and changing but often contentious relationships between the indigenous peoples and the Chinese population. After the First Sino-Japanese War between 1894-1895, Taiwan was ceded by the Qing government to Japan, becoming a new colonial administration under Meiji-era Japan. This history of the Japanese occupation of Taiwan highlights the mechanisms of colonization and imperialism that have a profound effect on the people of Taiwan to this day. The Japanese occupation of Taiwan was largely supposed to be based on two policies of “assimilation” and “equal treatment under one imperial view,” promising a vision of Taiwan as being akin to a home island of Japan. In practice, the Japanese killed thousands of Taiwanese who resisted colonial rule while collaborating with local elites to better secure their hegemony of the island. The colonial administration had a modernization program that expanded agriculture, building schools, and universities, building railways, expanding telegraph networks, police institutions, and introducing new entertainment such as motion pictures. Much of these infrastructures brought Taiwanese society into a modern era while also expanding exports of island resources such as rice and camphor, a material used for gunpowder, mainly for the benefit of the home islands of Japan. This investment in the life and economy of Taiwan was all for the benefit of Japanese industrialists, merchants, and the military, who needed railways, telephones, harbors, and many other networks to bring in military equipment and personnel while exporting Taiwanese goods. While many Taiwanese were afforded some privileges due to being seen as modern imperial subjects, the Taiwanese indigenous people were designated as seiban “wild savages” who needed to be assimilated, and any resistance against the Japanese met with eradication and displacement. Known as Takasagozoku (Formosan Aborigines), they were thought to be lacking in economic sensibilities to live in “regularly administered territories” of Taiwan. These harsh and discriminatory practices lead many indigenous groups to flee or fight Japanese occupation. The Musha Incident in 1930 was the last prominent uprising against the Japanese in which the Seediq indigenous people attacked a Japanese village, and in retaliation, the Japanese military killed over six hundred Seediq. This led to a change in aboriginal policies where the Taiwanese indigenous people were now considered imperial subjects in order to placate any further anti-imperialist sentiment. There was an increase of assimilation policies at the turn of the century of Taiwan, promoting Japanese culture, the Japanese language, and loyalty to the Emperor. By 1937 with the beginning of the war with China, throughout Taiwan, colonial efforts were made to change Taiwanese society into a purely Japanese one through incentives to the public while cracking down on Taiwanese cultural institutions. This included speaking Japanese, taking Japanese names, dressing in Japanese clothing, abandoning Chinese customs, and promoting loyalty to the Japanese Emperor. Towards the end of Japanese rule, over 70% of children in elementary schools were learning Japanese and Japanese customs. By 1941, the government encouraged Taiwanese men to serve in the Imperial Japanese military; many did volunteer or were conscripted. Between 1941-1945, two hundred thousand Taiwanese volunteered or were drafted into the military, with thirty thousand soldiers dying from various conflicts in China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Burma, Singapore, Borneo, and Okinawa. Around two thousand Taiwanese women were forced into sexual slavery by the Japanese military, and they were mostly young indigenous and Han Chinese women who were coerced by Japanese military personnel. As Ozaki Hotsuki, a Japanese journalist who was deeply critical of Imperial Japan, noted, the Taiwanese suffered despite being imperial subjects as they were, "...not to live as Japanese, but to die as Japanese", succinctly pointing out the hypocrisy of Japan's treatment of Taiwan. During World War II, Taiwan also served as a proxy for both Japanese and American conflicts and ambitions in East Asia. While never directly invaded by the U.S., such as Okinawa, Taiwan was a target for American military air bombs. The Taihoku Air Raid in 1945 was the largest Allied air raid, targeting modern-day Taipei, with a resulting death toll of approximately three thousand Taiwan civilians and the wounding of thousands more. For most Taiwanese, it became increasingly apparent that the Japanese would be defeated, and thus great uncertainty loomed over the future of Taiwan in terms of its eventual subsequent ruler. The Cairo Conference in 1943, a turning-point meeting of Allied powers led by Winston Churchill, Chiang Kai-Shek, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt, intended to give the territories that Japan had seized (Taiwan, along with Manchuria and Pescadores) to the Republic of China. While these intentions didn't all follow through following the Chinese Civil War, by October 1945, Taiwan was under the new governance of the Republic of China, ending fifty years of Japanese imperial rule. Like many colonial legacies, the history of the Japanese occupation of Taiwan had complexities of a colonized people who were part of the Japanese war machine. Many Taiwanese were at once soldiers and collaborators with Japan's war efforts while victims of colonial practices that suppressed their cultures and punished dissidents. Today, lingering issues with Japan exist, such as unpaid pensions of Taiwanese soldiers who were in the Japanese Imperial Army, reparations of the soldiers' bodies from Japan, and reparations for the increasingly few women who were under sexual slavery during that era. The Japanese occupation of Taiwan is tightly linked to the decades coming after the occupation ended, with the Republic of China becoming the new government of Taiwan, a change in government that held many hopes and anxieties of the Taiwanese people whose island have been under control by others for decades. Even though around 75 years have passed since the Japanese occupation, Japanese influences are still found in the culture around the island, and a long history of colonization informs the future of Taiwan. Sources: Barclay, Paul D. Outcasts of Empire Japan's Rule on Taiwan's "Savage Border," 1874-1945. University of California Press, 2018. Grajdanzev, A. J . “Formosa (Taiwan) Under Japanese Rule.” Pacific Affairs, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 311-324. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2752241. Morris, Andrew D. Taiwan's History: An Introduction. University of Hawaii Press, 2004. "台灣大百科全書." Wushe Incident - 台灣大百科全書 Encyclopedia of Taiwan. Accessed July 25, 2021. https://web.archive.org/web/20140325180546/http://taiwanpedia.culture.tw/en/content?ID=3722 Related book:

2 Comments

Richard Ho

6/11/2023 01:47:47 am

Your use of the term "Japanese occupation" is incorrect. The Treaty of Shimonoseki states in Article 2:

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

|

Pacific Atrocities Education

730 Commercial Street San Francisco, CA 94108 415-988-9889 |

Copyright © 2021 Pacific Atrocities Education.

We are a registered 501 (c)(3) charity. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>