|

by Peter Lassalle-Klein

The colonization of China was a long campaign involving the exploitation of the Chinese economy by the western powers, but mainly of Britain, France, and the U.S. Before this, China was at the center of the world economy throughout the 1700s due to their widely sought exports of porcelain, silk, and tea, all under the era of the Qing dynasty.[1]

However, the Qing Dynasty faced many issues and by the end of the 1700s, China was experiencing strains: a quickly growing population, a difficulty of food supply for this population, and a subsequent lack of centralized government control; all of which led to rebellions and a weakening of the dynasty’s power throughout their country.[2]

Alongside these strains, China also contracted many tolls due to the destruction caused by the Opium Wars and the presence of western powers in the country. They were forced to open ports to trade illegal contraband, they also had to permanently give up land just off of their coast to foreign powers, grant legal immunities to non-Chinese traders, and after the second Opium War, they were mandated to allow free movement of Christian missionaries throughout the country. Though, by 1860, due to the imposition of British, French, and U.S. powers in China, it could be considered little more than an international colony.[3] By the early 1900s, the British Empire (now called the United Kingdom), the German Empire, Russia, France, the United States, Japan, Italy, and Austria-Hungary were all present in China, “defending their interests” from the rebels of the Boxer Rebellion in Beijing.[4] In fact, it was one of the few times in history these countries allied with one another: to end the resistance to their western influences in China. The united forces assaulting Beijing did not even do so to defend its people but to see which national army gained the glory of relieving the city of the Boxers.[5] The forces killed the Boxers in Beijing and subsequently looted the entire city as representative armies of eight different countries destroyed Beijing apart. Even Yuanming Yuan (Old Summer Palace), the imperial expanse of palaces and gardens which spanned 3.5 square kilometers, was thoroughly sacked. Its remains still lie in 47 different museums around the world, including the British Museum in London.[6] By the end of the weeks of looting, Beijing was in shambles. China had all the qualities of a colony–international powers dominated it, its economy was used to fund other countries, and an outside religion was being spread through colonial missionaries–it was a colony in anything but name. China transitioned from being the most powerful economy in the world before the Opium Wars to its GDP dropping by half just a decade later.[7] This is reflective of the damage China took from the Opium Wars, but the British colonizers would not let their main source of profit stay broken for long. Through colonization, China’s economy was manipulated by the western powers: the economy fiscally grew, but the wellbeing of the Chinese since the funds of the economy was sent directly to America, France, and the British Empire.

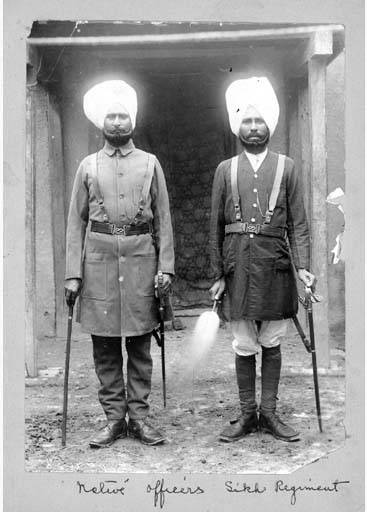

One of the most direct effects on the Chinese economy during the colonial era was the role of Hong Kong just after the Opium Wars. Hong Kong was originally a barren island populated by a few thousand farmers and fishermen when it fell under the sway of the British Empire by force in 1841 and developed into a full-fledged territory after the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842.[8] From that point onward it remained under absolute British control, with a notable presence of the British military. This military/police force, however, was not made up of just English troops, but Indian soldiers as well.[9] The British Empire’s colonization of India was in full effect due to the industrialization of the opium trade, which was produced from Indian poppies in mass quantities. Along with the troops came Indians emigrating from British-controlled India, which pushed the development of Hong Kong through the jobs of building ports, homes, and other colony necessities for a trade city. Hong Kong quickly became the launching point for the British’s business in mainland China as they profited off of the labor of those they had already colonized.

Sikh officers dressed in their daily uniforms in Tientsin (now Tianjin), China. “Officers of the Sikh regiment, Tientsin ?, 1900,” by Robert Henry Chandless. Source: University of Washington. Via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Officers_of_the_Sikh_regiment,_Tientsin_%3F,_1900_(CHANDLESS_24).jpeg

The issue of colonization and China’s economy is a complicated one. Some believe that colonialism, through the suppression of another’s culture for monetary gain, developed China’s economy. This perspective argues that by forcing society to open its borders and ports to trade, the western powers stimulated the economy in a very direct way. Professor Mohammad Shakil Wahed at the University of Reading presents this pro-colonial perspective, saying, “The Middle Kingdom [The Qing Dynasty] would have been in isolation for many more years and might have remained in some form of ‘Dark Age’ without the timely imperial intervention.”[10] Professor Wahed also recognizes the issue with this perspective is that those who argue this are often very critical of China for “not being able to take enough goodness from the west.”[11] This pro-colonial view of colonialism is an entirely positive thing that is a biased view that is critical of any non-western influence and does not recognize the damaging impacts of colonialism in China and its public. Almost all of the arguments for a pro-colonial perspective are biased in this way against the Chinese: condemnatory of any values that did not originate from the West. Therefore, when they are used in a discussion of China’s economy, they present an unresolvable conflict of interest.

From an economic standpoint, pro-colonists argue that colonization is what reinforced the importance of capitalism and trade in China.[12] This is due to information suggesting such: China experienced a steady growth of agricultural output and income between the 1870s to the 1940s, which supplied its growing population with the food needed for continual growth.[13] Furthermore, China experienced growth with the introduction of modern machinery as the west demanded more goods to be sent abroad. This introduction of factories and machinery, however, did not create as much as an immediate effect as it had in Europe. China did not experience an industrial revolution like Europe did, since “the production output of modern industries could not exceed the output of the traditional handicraft industry. Even during the mid-1930s, the total value output of native handicrafts was more than three times that of the modern machinery-based industries.”[14] Although pro-colonists claim industrialization did develop to the Chinese economy, historians state that this did not occur until after the colonial era after the western powers were ousted from China: “This trend of industrialization did not turn into an industrial revolution like the one that occurred in Europe.”[15] Both the Qing state and the Chinese people were very unwelcoming to western influence, and understandably so. Most of the goods being produced in China were traded or invested in foreign interests, rather than in Chinese interests.[16]

References:

1. “China and the West: Imperialism, Opium, and Self-Strengthening (1800-1921) - Asia for Educators, Columbia University.” http://afe.easia.columbia.edu. Accessed 30 Sep., 2019. 2. ibid. 3. “The Colonization of China - Aspirant Forum.” 14 October, 2014, https://aspirantforum.com/2014/10/21/colonization-of-china/. Accessed 12 Sep., 2019. 4. Fleming, Peter. The Siege at Peking: The Boxer Rebellion. New York, NY: Dorset Press, 1959. 5. ibid, 200. 6. “Old Summer Palace marks 157th anniversary of massive loot - Chinadaily.” 19 October, 2019, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/culture/2017-10/19/content_33436716_2.htm. Accessed 28 October, 2019. 7. Kalipci, Müge. "Economic Effects of the Opium Wars For Imperial China: The Downfall of an Empire." Bolu Abant İzzet Baysal Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 18 (2018): 291-304. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/basbed/issue/39758/470806. Accessed 16 Sep., 2019. 8. “The Opium Wars in China - Asia Pacific Curriculum.” 2019, https://asiapacificcurriculum.ca/sites/default/files/2019-02/Opium%20Wars%20-%20Background%20Reading.pdf. Accessed 24 Aug., 2019. 9. “Hong Kong Sikhs - Angelfire.” 1 June, 2006, http://www.angelfire.com/planet/hongkongsikhs/FLAGTOP-0608141522-25-1-1841-hongkongsikhs.html. Accessed 17 Sep., 2019. 10. Wahed, Mohammad S. “The Impact of Colonialism on 19th and Early 20th Century China.” Cambridge Journal of China Studies 11, No. 2 (2016): 26. https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/257410. Accessed 17 Sep., 2019. 11. ibid. 12. ibid 13. ibid., 28 14. ibid., 29 15. ibid. 16. Kalipci, Müge. "Economic Effects of the Opium Wars For Imperial China: The Downfall of an Empire." Bolu Abant İzzet Baysal Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 18 (2018): 291-304.

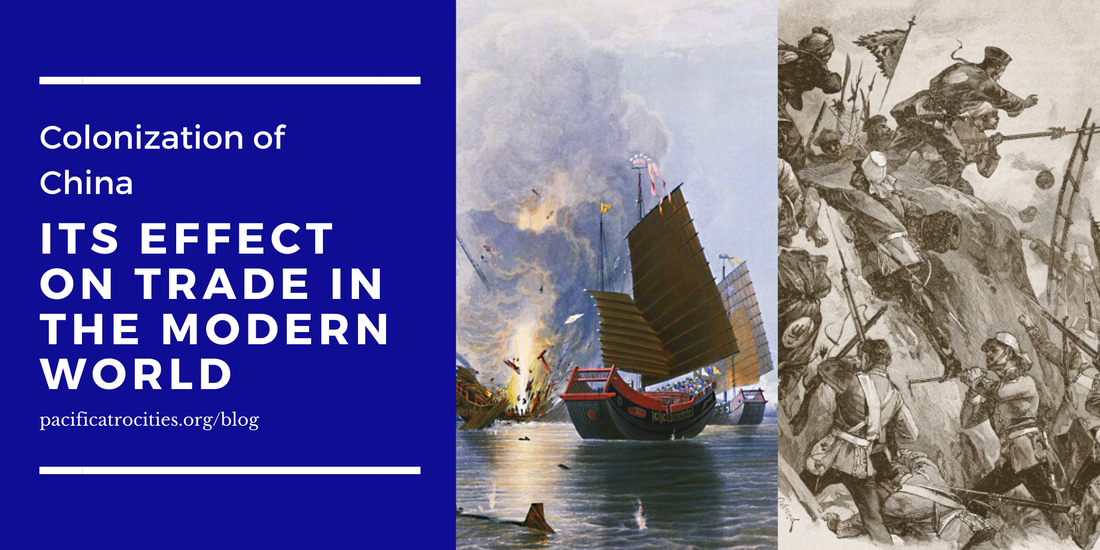

Header images

Left: The East India Company iron steam ship Nemesis, commanded by Lieutenant W. H. Hall, with boats from the Sulphur, Calliope, Larne and Starling, destroying the Chinese war junks in Anson's Bay, on 7 January 1841. An engagement in the First Opium War (1839-42), showing the ‘Nemesis’ (right background, in starboard broadside view) attacking a fleet of Chinese war junks in the middle ground. The war junk third from the left is shown being destroyed with splinters flying up into the air. Two rowing boats with Chinese passengers watch from the left foreground. Various men can be seen overboard and clinging on to debris throughout the scene. The lettering below includes lists of dimensions. PAH8193 and PAH8893 are additional copies, both hand-coloured, and the print is from an oil painting by Duncan presented to the Williamson Art Gallery at Birkenhead in 1925, with another showing Prince Albert visiting iron ships off Woolwich Dockyard. They were a gift from Alderman J.W.P. Laird, one of the Birkenhead shipbuilding family who built the 'Nemesis' and others of the vessels shown in them. On 7 January 1841, the 'Nemesis' of the Bombay Marine (the East India Company's naval service), commanded by William Hutcheon Hall, with boats from the ‘Sulphur’, ‘Calliope’, ‘Larne’ and ‘Starling’, destroyed Chinese war junks in Anson's Bay, Chuenpee, near the Bocca Tigris forts guarding the mouth of the Pearl River up to Canton. British forces then captured the forts themselves. Hall was a Royal Naval master at the time. He had steam experience and had been privately engaged by John Laird to command the 'Nemesis', which the latter had built experimentally as the first fully iron warship, and was so successful in it in China that in 1841 he was specially commissioned as a Naval lieutenant. He went on to later Royal Naval service as a captain in the Crimean War and was a retired admiral at his death in 1875. His portrait (BHC2733) and papers are also in the Museum collection. Created: 29 May 1843 by Edward Duncan- Public Domain https://visualizingcultures.mit.edu/opium_wars_01/ow1_gallery/pages/1841_0792_nemesis_jm_nmm.htm Right: British troops storm the Taku Forts, China, in 1860, in Second Opium War. Created: 1860 by William Heysham Overend- Public Domain Related Books

1 Comment

Abhilash Kumar

3/20/2022 11:35:11 pm

Hi,

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

|

Pacific Atrocities Education

730 Commercial Street San Francisco, CA 94108 415-988-9889 |

Copyright © 2021 Pacific Atrocities Education.

We are a registered 501 (c)(3) charity. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>