|

by Junyi Han

In May 1942, the rainy season in Burma just began to reveal its true color, soaking lands with nightmarish thunderstorms. In the meantime, tens of thousands of soldiers from the Chinese Expeditionary Force were suffering from a disastrous retreat in the jungle.

(continued) Gu Luo, a soldier serving in the Fifth Army wrote in his diary: “The jungle covered everything for miles, leaving us deadly thirsty…The soldiers are all in rags and look very gaunt. Everyone is carrying a bag of rice, a water-can, a diesel tin, and in the other hand, a walking-stick…Because we haven’t had any oil for a month, my stools are very hard and my anus has split” (Mitter 640). Luo only provides us with a sketch of this withdrawal. In fact, about 30,000 soldiers died in this foreign jungle (Wangyi). The tremendous death toll urges us to question how and why this tragedy happened. Historical records suggest that this military disaster was primarily caused by a split among the Allied leaders and it was exacerbated by the extreme climate in Burma.

In early 1942, the situation in Burma was unfavorable to the Allied forces. In late April, the Japanese troops continued advancing in eastern Burma and successfully seized Lashio on April 29th. Under such circumstances, Joseph Stilwell, the commander of the American Army Forces of the China-Burma-India Theater and the Chiang Kai-Shek’s chief of staff, was concerned that the Allied troops in this region would be destroyed by the Japanese army and therefore wanted to initiate an imminent retreat (Chen). However, a split between Joseph Stilwell and his superior Chiang Kai-Shek broke out as they were setting out the withdrawal plan. While Stilwell wanted to bring his troops to India instead of back to China, Chiang was “aghast when he heard the news that his chief of staff had ordered a substantial part of his army into another country, and wondered whether Stilwell had lost his resolve because his proposed attack in Burma had gone so wrong” (Mitter, 637). Chiang then reversed Stilwell’s order, commanding the generals to lead their troops to assemble in Myitkyina, a town in northern Burma. Stilwell was determined to leave. He formed a party of about eighty people – including American, Chinese, and British soldiers, Indian engineers, and Burmese nurses – and headed to India (Mitter, 638). While Stilwell’s group managed to arrive in India without any deaths, the rest of his troops were not as lucky. For instance, general Yuming Du, the commander of the Fifth Army, decided to follow Chiang’s order and led his troops to Myiktyina. For the Fifth Army, the most lethal threat on their way did not come from the Japanese troops, but from nature. When Du decided to dispatch his troops into the Burmese jungle, he had no idea how terrifying the journey could be. In early May, because the communications broke down, they decided to move northwest into Mandalay and soon got lost in the jungle. The rainy season in Burma came along with extreme weather. Massive thunderstorms soaked soldiers to the skin. Moreover, everywhere they go, insects attacked them ruthlessly. The longer they stayed, the conditions became even worse. The soldiers were too exhausted to carry their own weapons. The weapons were destroyed and abandoned so that they would not be captured by the Japanese troops. Luo recalled that as his division wandered in the jungle, he saw corpses scattered everywhere. Their company cook was missing and the remains of his body were found half-eaten, supposedly by tigers (Mitter, 639). By the middle of June, the soldiers were bogged down into a more desperate situation. They were “starving, digging up roots to try and survive; meanwhile the monsoon rains poured down every day. Even when supplies were dropped in the area from the air, tragedy struck, as some soldiers were hit and killed by the falling boxes. More then died from eating too fast after a period of long deprivation” (Mitter, 641). Other divisions of the Chinese Expeditionary Force also went through extreme hardships, and a large number of soldiers were wiped out by assaults from native people, Japanese attacks, and disease. Recently, the skulls of three female soldiers were found in a native Burmese tribe. The chief of the tribe said these skulls were used as medicine ladles for women who suffered from difficult labor (Sina). These skulls have been taken back to China. Now they are kept in Dianxi Anti-Japanese War Memorial Hall located in Yunnan, China. There were many more soldiers lost in the jungle and remained unknown in a foreign land. Overall, the retreat was a fatal disaster. It led to the death or injury of about 25,000 Chinese troops (the exact number is unclear) along with over 10,000 British and Indian troops (Mitter 642). This failure was rooted in the distrust among the Allied leaders, and the death toll substantially increased due to the extreme weather in Burma. This massive withdrawal caused severe damages to the Allied defense in the China-Burma-India Theater. The supplies to China were cut off as the Japanese troops seized the Burma road. Therefore, the National Government led by Chiang became even more isolated. References:

While you are here, we have a small favor to ask. PAE was founded as a nonprofit in 2014 because we knew the mainstream media wouldn't cover the forgotten voices of the Pacific Asia War. Today, the support from our readers makes up about 2/3 of our budget. This support allows us to dig deep on stories from the past that matter. If you value what you are reading from us, please contribute to make this possible.

Related Books

1 Comment

Yogesh Pawar

7/8/2024 07:20:57 am

Hi, I intend to use some of the footage from your channel in my documentary film, from the following video:

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

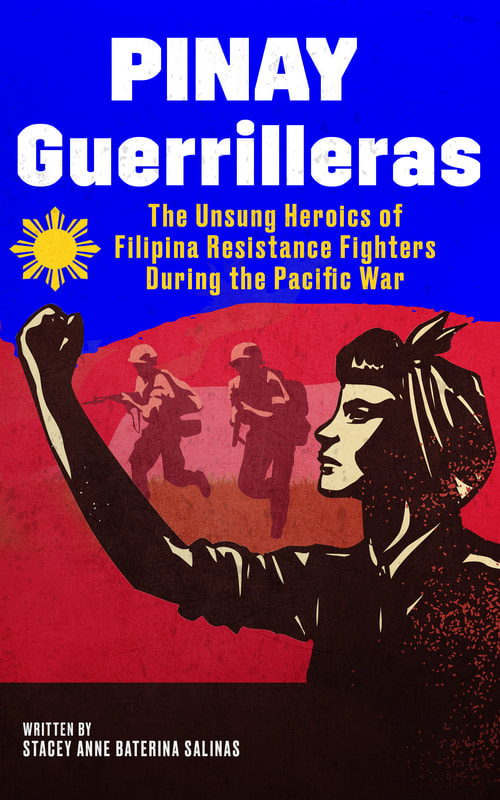

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

|

Pacific Atrocities Education

730 Commercial Street San Francisco, CA 94108 415-988-9889 |

Copyright © 2021 Pacific Atrocities Education.

We are a registered 501 (c)(3) charity. |

- Home

- Stories

-

Internship

- Summer 2024 Internship

- Summer 2023 Internship

- Fall 2022 Internship

- Summer 2022 Internship

- Summer 2021 Internship

- Fall 2020- Spring 2021 Internship

- Summer 2020 Internship

- Fall 2019 Internship

- Summer 2019 Internship >

- School Year 2018-2019 Internship

- Summer 2018 Internship >

- Fall 2017 Internship

- Summer 2017 Internship >

- Books

- Archives

-

Resource Page

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>

- Unit 731 - Guide >

-

Philippines' Resistance - Guide

>

- Philippines World War II Timeline

- The Japanese Invasion & Conquest of the Philippines

- Bataan Death March

- Formation of Underground Philippines Resistance

- Supplies of the Guerrilla Fighters

- The Hukbalahap

- Hunter's ROTC

- Marking's Guerrillas

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines of Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- The Aetas

- Chinese and Filipino-Chinese Nationalist Guerrilla Units

- The Female Faces of the Philippine Guerrillas

- Rising Sun Flag - Guide >

- Pinay Guerrilleras - Guide >

- Fall of Singapore - Guide >

- Three Years and Eight Months - Guide >

- Siamese Sovereignty - Guide >

- The Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial - Guide >

- Unit 731 Cover-up : The Operation Paperclip of the East - Guide >

- Marutas of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Prince Konoe Memoir - Guide >

- Competing Empires in Burma - Guide >

- Battle of Shanghai - Guide >

- Ishi Shiro - Guide >

- Taiwan The Israel of the East - Guide >

- Seeking Justice for Biological Warfare Victims of Unit 731 - Guide >

- Rice and Revolution - Guide >

- Clash of Empires - Guide >

-

Hunger for Power and Self-SufficiencyI - Guide

>

- The Influence of War Rations on Post-War Culinary Transformations

- How World War II Complicated Food Scarcity and Invention

- American Military Innovations

- Government-Sponsored Food Inventions in Europe during World War II

- Feeding the Army: The Adaptation of Japanese Military Cuisine and Its Impact on the Philippines

- Mixed Dishes: Culinary Innovations Driven by Necessity and Food Scarcity

-

Denial A Quick Look of History of Comfort Women and Present Days’ Complication - Guide

>

- The Comfort Women System and the Fight for Recognition

- The Role of Activism and International Pressure

- The Controversy over Japanese History Textbooks

- The Sonyŏsang Statue and the Symbolism of Public Memorials

- Activism and Support from Japanese Citizens

- The Future of Comfort Women Memorials and Education

- Echoes of Empire: The Power of Japanese Propaganda - Guide >

- Lesson Plans >

-

Supplementary Research Guides

>